"T-3 hours and counting" found Space Shuttle Challenger nose up on a giant

launch pad near Orlando, Florida. Its massive gas tank stood 15 stories high, filled

with enough fuel to propel a team of astronauts far beyond the path of commercial

aircraft to the mysteries of outer space.

One by one, astronauts entered the orbiter, the flying machine that would hold and

protect them as they circled Earth at mind boggling speeds. Strapped to a seat in

the orbiter's crew cabin, 36-year-old Bonnie Dunbar braced herself. As a girl, she

dreamt of building spaceships or rocketing into orbit. To many, her odds would have

seemed insurmountable. Growing up, Dunbar split time chasing cattle through the

Rattle Snake Mountains of the Yakima Valley, raising steers, and packing corn for

ten cents an ear. On a fall day in 1985, however, the little girl from Outlook,

Washington was just six seconds shy of defying the most improbable odds, ending

the most unlikely journey, and living out her dream.

So mighty it would take "39 train engines to produce the same amount of power,"

Challenger thundered away from Kennedy Space Center the day before Halloween.

Its intense and forceful rumble could be felt for miles. Leaving a towering cloud

of smoke in its wake, the rocket slashed through clouds and miles of Earth's atmosphere

traveling faster than the speed of sound.

Gone were the rocket boosters, jettisoned two minutes and six seconds after liftoff.

The bumpy ride smoothed. Six minutes later, the three main engines shut down. The

giant external tank cut loose for its fiery return into Earth's atmosphere. Shuttle

Challenger reached the shadowy darkness of low Earth orbit.

The orbiter began to sail through the vastness of space, freefalling on a circular

arc identical to the curvature of the Earth. Inside, another American woman proved

the skeptics all wrong. Bonnie Dunbar had made it to space after all.

The Good Life

The young astronaut beams at nine months.

Dunbar personal collection.

The young astronaut beams at nine months.

Dunbar personal collection.

One of the first times Bonnie Dunbar sat perched above the surface of Earth, she

was in a tree house of her own making. The creation, fastened together with big

burlap sacks, spare wood, and nails, surely wouldn't have held up in the harshness

of space. But it was a childhood masterpiece, proudly rooted in a tree on the Dunbar

property in the scenic Yakima Valley. The storybook image was one of many.

Dunbar can still smell the fresh mix of spearmint, peppermint, and grapes wafting

through the open windows of the school buses every fall. She can hear her family

and friends singing as they huddled around the campfire after a roundup and a big

cookout. She remembers discovering hidden wonders of the countryside by horseback,

when a whole new world stretched out in front of her.

Theirs was a blessed childhood, says Dunbar, looking back at life with two younger

brothers and a younger sister. The family homesteaded just a few miles outside of

Outlook. The small community offered a sense of neighborliness and responsibility

that money just can't buy.

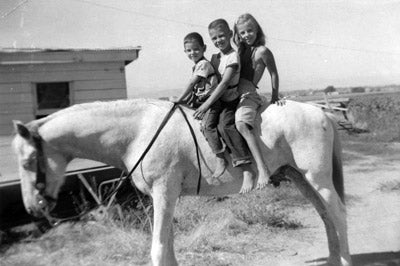

With brothers Gary and Bobby in the cornfields.

Dunbar personal collection.

With brothers Gary and Bobby in the cornfields.

Dunbar personal collection.

By age nine, the Dunbar children drove tractors, worked the fields, and measured

time by the season. Every spring, they picked rocks from the fields and tossed them

into an old trailer bed to free up the land for plowing and planting. Bonnie learned

to make an honest living, sorting asparagus for minimum wage and packing corn for

ten centers an ear. It was a farm family’s life.

But cattle were the Dunbar family’s bread and butter. Up with the Sun, Bonnie, Bobby,

and Gary trailed Hereford cattle and rode fence up and down the Rattlesnake Mountains.

They branded steers every Memorial Day and showed them at the local fair in Grandview.

Sometimes, you could see them out milking cows before school.

Come winter, the entire family pulled together. Bonnie and Bobby learned how to

protect themselves at a gun safety school. "It can get cold, you can get lost, you

can hurt yourself," Dunbar remembers. "You're out at the base of the Rattle Snake

Mountains-there are coyotes, there are rattlesnakes."

Younger brothers Bobby and Gary through ranchland of Central Washington. Despite humble beginnings, Bonnie proved she had the "right stuff" to fly in space.

Younger brothers Bobby and Gary through ranchland of Central Washington. Despite humble beginnings, Bonnie proved she had the "right stuff" to fly in space.

The Dunbars didn't quite live high on the hog either. In 1949, months before six

and one-half pound Bonnie Dunbar arrived at Sunnyside's Valley Memorial Hospital,

her pregnant mother Ethel prepared to forge the waters of first-time motherhood

while living in a tent. "Two sheep herder huts pushed together” is how Dunbar puts

it. It took a full day’s work to tow the huts from Condon, Oregon, she says. The

family lived without running water and many modern conveniences for years after

Dunbar was born. By high school, the Washington native had watched all of two movies

in a theater.

But there was something magical and inspiring, says Dunbar, about the togetherness

out on that ranch. There was great satisfaction in seeing what you can do with a

day, working hard and working together. Young Bonnie was developing the tireless

work ethic that would make her career and the self confidence that would ensure

she stayed the course. As it turned out, the most humble childhood was chocked full

of riches for a bright girl with dreams. It was years before Dunbar would step onto

a Florida launch pad. But she was on a cattle ranch a world away, acquiring the

grit and smarts of an astronaut.

Editor's Note

Factual information in this biographical profile

and oral history is current as of September, 2009 and supplied by the National Aeronautics

and Space Administration.