A sailboat racer and a pilot, Robert F. Utter has sailed

the sea and soared the sky, but his voyages of discovery have also taken him to

what he describes as the "sacred sanctuary of the conscience." His life's work is

to be a man of faith and a judicious judge.

On March 30, 1995, after 23 years on the Washington Supreme Court, he told the chief

justice he was resigning. He could have walked across the street, up the steps to

the Capitol and through the marbled halls to Gov. Lowry's office. He could have

called a news conference with a gaggle of reporters and TV cameras. But that didn't

feel right either. This decision was too personal. Instead, he composed a formal

letter, sent it over to the governor, then called the veteran Associated Press correspondent,

John White, who got the scoop because their sons once swam on the same team.

"I have reached the point where I can no longer participate in a legal system that

intentionally takes human life," Utter told the governor. "...We are absolutely

unable to make rational distinctions on who should live and who should die."

In 1971, when he was 41, Utter had become one of the youngest justices in state

history. He dissented in two dozen death penalty cases before concluding he was

tilting at windmills. Killing to satisfy its visceral appetite for retribution,

the system "is fatally flawed," the judge said. "Like lightning," the death penalty

"strikes some but not others in a way that defies rational explanation." Worse yet,

Utter asserts, an allegedly "modern civilized society" has executed at least 48

innocent people in the past four decades. Then there are the close calls: More than

100 people on Death Row across America have been freed in recent years based on

DNA tests and other new evidence.

Utter believes that a life sentence without the possibility of parole protects society

just as well - and at far less expense. In 2007, New Jersey became the first state

to ban executions since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976.

Utter notes that the governor there commuted the death sentences of 10 men to life

imprisonment without the possibility of parole in the wake of the revelation that

each death sentence cost the state $4.2 million. "It's 10 times more expensive to

kill them than to keep them alive," Donald McCartin, once known as California's

"Hanging Judge of Orange County," told reporters early in 2009. A month later, New

Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson repealed the death penalty in his state, saying, "I

do not have confidence in the criminal justice system as it currently operates to

be the final arbiter when it comes to who lives and who dies for their crime…"

While his stand on the death penalty is the most dramatic chapter in a 55-year legal

career, Utter's jurisprudence is prolific. His longest lasting contributions may

well be in the areas of state constitutional law, environmental law, criminal procedure

and eliminating bias from jury instructions. In 1978, he wrote an opinion that established

a battered woman's right to self defense. He was the lone proponent of the "battered

woman theory" when the debate began behind closed doors, but the eloquence of his

arguments carried the day.

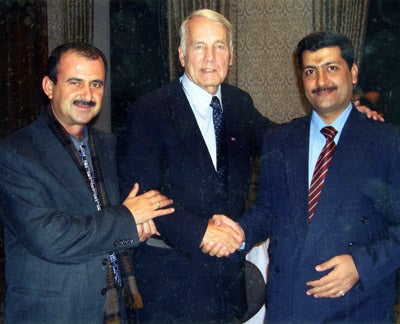

Justice Utter is congratulated by former

governor Dan Evans in 1997 as the YMCA's Youth & Government program announces

it has named its top award in his honor. It is presented annually to "an individual

of unquesti onable integrity who exemplifies outstanding citizenship, leadership

and character." Chris Gregoire, then Attorney General, looks on at center.

Justice Utter is congratulated by former

governor Dan Evans in 1997 as the YMCA's Youth & Government program announces

it has named its top award in his honor. It is presented annually to "an individual

of unquesti onable integrity who exemplifies outstanding citizenship, leadership

and character." Chris Gregoire, then Attorney General, looks on at center.

Utter's advocacy for victims' rights and compensation counters the charge that he

is a bleeding-heart liberal. For 40 years, he has been saying that victims too often

are the forgotten people in the criminal justice system. "Once the immediate reactions

of anger, fear and vengeance have been verbally expressed" in the wake of a crime

"the average citizen washes his hands of all responsibility and leaves it to the

official avengers." The system's "primary client is the victim," the judge told

the Seattle Rotary club in 1972 in a speech that made headlines around the state.

It was one of many such talks he would give in a typical year - at PTA meetings,

Prayer Breakfasts and Bar Association gatherings. Early on, he dedicated himself

to harnessing what he calls "The power of one plus One."

Utter is a tireless mentor. He was a co-founder in 1958 of the Big Brothers chapter

in Seattle, the state's first; helped launch the Thurston-Mason chapter in 1982

and played a key role in the YMCA's Youth & Government program, which in 1997

named its top award in his honor. It is presented annually to "an individual of

unquestionable integrity who exemplifies outstanding citizenship, leadership and

character." (The 2009 winner is Secretary of State Sam Reed.)

Although Utter has won countless awards, you'll find only a couple on his shelves.

He takes his satisfaction from the lives he has saved or changed. From the bench

and on the streets he saw "the countless confused, accused, misused, strung out

ones and worse," as Bob Dylan once wrote, and he felt compelled to intervene.

In the years since he left the court, Utter has been engaged in judicial, civic

and political activism on multiple fronts around the world. He has a national reputation

as a legal scholar and mediator and an international following as a teacher. The

courage of judges in emerging democracies inspires him. Some of his students have

been gunned down or blown to bits in places where theocratic fascists fear an independent

judiciary. One was shot and killed as he drove to work, and an insurgent group boasted

that the murder ''would make God and the Prophet very content.''

Close friends and loved ones have seen what Utter acknowledges is an "undercurrent

of sadness." There have been dark days and long nights when he has struggled with

the heartache of a daughter born with serious physical and emotional challenges.

He is appalled by hate, hunger and injustice and has no easy answer for the never-ending

question of why bad things happen to good people. He agonized over his discovery

that a vulnerable young woman had been sexually victimized by a minister he trusted.

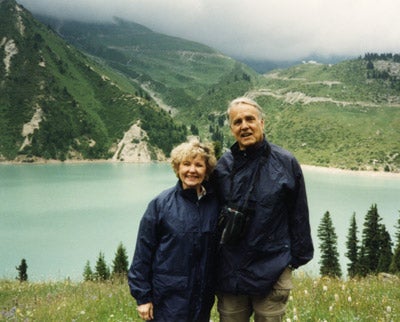

Bob and Betty Uttter on the deck of

their sailboat, Daring Spirit.

Bob and Betty Uttter on the deck of

their sailboat, Daring Spirit.

He has waged a winning battle with cancer and Parkinson's disease. Others have endured

far worse, he emphasizes, adding that pain can be a profound "teaching lesson."

Life is a celebration, the judge believes, "and it should be lived that way, no

matter how much pain is there."

Through it all he has been sustained by his faith and the love of his life, Betty

Utter - teacher, friend, fellow sailor, the woman who never balked when he brought

home stray kids who needed a hot meal and the intervention of a caring grownup.

Betty is a remarkable person in her own right. She was a highly regarded teacher,

taught counseling at Saint Martin’s College and served as president of the Associated

Ministries of Thurston County. In the 1970s, she helped launch an ecumenical religious

education program for the mentally handicapped. It grew to embrace about a dozen

churches in Thurston County. When they lived in Seattle, Friends of Youth, a church-sponsored

shelter for teen-age boys, was one of Bob and Betty’s early causes. In their retirement

years, the Utters have been working with the Rural Development Institute, which

promotes social justice by helping poor people around the world secure land rights.

Betty also has volunteered as a mediator with the Dispute Resolution Center of Thurston

County.

Betty says Bob was "tall, dark and handsome" when they first met on campus at Linfield

College in Oregon in 1949. He's gray now and quips that with age he has also become

"less tall" - but she's "still short." He's a striking man, with vivid blue eyes,

a gentlemanly demeanor and a puckish sense of humor. Especially in the days when

he puffed a pipe, he looked just like the judge you'd get if you called Central

Casting.

He is soft-spoken, sometimes hesitating in mid-sentence to choose just the right

words. His smile is so engaging, his manner so unpretentious that you'd never guess

he is fundamentally shy. You'd never imagine that in high school he was an underachiever

with no real notion of what he'd like to be when he grew up. Well, he knew one thing

for certain: Despite his father's prodding, he didn't want to join him selling life

insurance.

Early heartbreak

Robert French Utter was born in Seattle on June 19, 1930. A few months before his

sixth birthday, his mother died in childbirth, together with the infant son she

was carrying. Besse Utter was 28 years old when she bled to death on April 7, 1936.

It was a devastating blow to her husband and the two young sons she left behind.

In 1937, John Utter remarried. Bob's stepmother was a religious education director.

Despite her strong faith, acquiring two young sons was as difficult for Elizabeth

Utter as it was for Bob and his younger brother, Fred. She wasn't a bad person,

Bob emphasizes, but she could never replace the mother he had lost. Happily, in

her last years, they reconciled completely. But when a first grader loses his mother,

he carries some of that heartbreak and insecurity for the rest of his life. In grade

school especially, Bob felt like a "wounded bird."

Baptized at the age of 12, Bob was a somewhat reluctant churchgoer as a teenager.

He knew his Bible, but the sermons weren't that stimulating. He was already bored

and bemused by tedious doctrinal dustups - "sprinkling vs. dunking," for instance,

as he puts it wryly. He found literature, history and politics a lot more interesting.

The highlight of his teenage years came in 1948, when as a senior at West Seattle

High School he participated in the second annual Youth Legislature in Olympia. "It

was the revelation that a whole new world existed. I found out how government was

supposed to work." During his career on the bench, Utter served as president of

the Youth & Government Board for 13 years.

In 1948, he was off to Linfield, the Baptist school at McMinnville. After two years,

he opted to transfer back home to the University of Washington, where he majored

in English Literature and Political Science. During his junior year, he also weighed

the idea of becoming a minister, but "didn't feel that strong of a calling." In

that era, a promising student could gain "early entry" to the UW Law School without

a four-year degree. That intrigued him. Supreme Court Judge Matthew Hill was a member

of the Seattle First Baptist Church and Utter concluded that a law degree would

be a good fit for a career in public service. The Korean War temporarily changed

his plans. Utter enlisted in the Air Force the summer before he began law school,

hoping to become a fighter pilot. A bum shoulder ended that idea and put him back

on campus. (Some 30 years later, he got his pilot's license and went on to earn

instrument ratings. Flying turned out to be fun, but less spiritual than sailing,

although Utter figured he must be on the right side of the Lord when he safely made

a wheels-up landing on the rain-slickened main runway at the Olympia Airport in

his Cessna 210.)

The Utters on their wedding day, December

28, 1953.

The Utters on their wedding day, December

28, 1953.

Betty Stevenson, a petite girl who was as bright as she was pretty, had also returned

home to Seattle and the UW to pursue her teaching degree. They had dated during

his sophomore year at Linfield. This time they fell in love and were married on

Dec. 28, 1953. "We bought a sailboat before we bought a house," Bob notes. "We had

our priorities straight."

Graduating from law school in 1954, Utter jumped at the chance to become Judge Hill's

law clerk at the Temple of Justice in Olympia. Matthew Hill, then 60, was once described

by an admiring press as "a tireless worker in civic, church and charitable affairs,

and a public speaker of wide repute." The last part was particularly true. Hill

loved to give speeches on every imaginable topic, from politics to parables. Earlier

in his career, the Republican had sought election to the State Legislature and Congress,

losing to future Washington State Democratic icon Warren G. Magnuson in 1938. Being

a judge was Hill's real calling. Fatherly and wise, he saw to it that his law clerks

- especially good Baptist boys like Bob Utter and Charlie Smith, another future

judge - got a wide-ranging education not only in jurisprudence, but in morals and

manners. Being Judge Hill's law clerk was a lot like being an admiral's aide-decamp.

You stayed up late, got up early, made sure your i's were always dotted and also

did the driving. It was a great year.

After 18 months as a deputy with the office of "Mr. Republican," King County Prosecutor

Charles O. Carroll, Utter joined a Seattle law firm in 1956. The job offered a lot

better pay and the learning experience of dealing with a broad base of clients.

His spare time was devoted to helping young people, church activities and starting

a family of his own with Betty. Then their first of three children, Kim, was born

with multiple handicaps, including the inability to cry until a surgical procedure

was done. The young couple was under enormous stress, emotionally and financially.

A phone call put them at a life-changing crossroads. It was a King County Superior

Court judge who had been impressed with 29-year-old Bob Utter's intelligence and

poise in his courtroom. Would Bob like to become a Superior Court commissioner assigned

to Juvenile Court? Utter didn't even know where the Juvenile Court was, much less

a lot about the laws governing juvenile delinquency. What he did know was that he

cared about kids and felt a calling to make a difference. Lawyers, after all, are

supposed to help people. Still, the job paid half as much as he was making with

the law firm. Would that be fair to his family? Their daughter clearly would need

ongoing medical attention.

"Take all the time you want to decide," the judge joked, "but we have to know tomorrow."

He and Betty talked about it, prayed about it. They decided it could be the chance

of a lifetime - or maybe a disaster. But they were young, imbued with faith and

concluded that if he didn't give it a try they would always wonder what might have

been. "So within 24 hours the course of my life was dramatically changed," Utter

recalls. And for the better, too, as it quickly turned out, because he immediately

encountered a boy who needed a stand-up man in his life.

Into his court one day in 1959 came Charles Russell, a fatherless 15-year-old who

had shot his mother's boyfriend to stop him from beating her. "Over the years, I've

always told Charlie the only mistake he ever made was just shooting him in the foot,"

the judge quips. "I could tell that he was a kid with a world of potential. We found

a spot for him at the Jessie Dyslin Boys Ranch. I had good friends with deeper pockets

who were interested in helping me help troubled kids."

"Until I met Bob Utter, I had no future," says Russell, now 66. "I couldn't really

read or write and I was getting into a lot of trouble. I had third- or fourth-grade

reading skills. By intervening in my life, he gave me a series of chances, and that's

important because one chance doesn't always work, especially with kids. For me,

there was no one thing that turned my life around. It was a cascade of events and

a series of chances… The Boys Ranch was important, but it was Bob who was always

there. I was slightly dyslexic, but I could do chemistry and math and he encouraged

me. I didn't have anybody else to call."

At Washington State University, Russell earned degrees in biochemistry, zoology

and entomology. ("That's bugs," he explains.) Then he earned a Ph.D. in ecology.

"I've never gone where I thought I was going to go," he says. "I taught at the University

of Costa Rica and eventually worked on a road through the mountains of Peru, then

on a dam project in El Salvador. I went from crops to forestry to infrastructure

projects." Russell now owns a tour company - Let's Tour Seattle - working with cruise

ships and museums. He and Utter talk often. "I'm constantly amazed at his level

of morality - his true belief in people who I would have given up on a long time

ago. Sometimes I shake my head at his - I can't call it naiveté. It's just faith."

The tears well up in Utter's eyes when he recalls all the Charlies he has met. His

only regret is that he couldn't help them all. Betty has always shared Bob's commitment

to helping children. But there were times, she admits, when Bob's cheerful line,

"Guess who's coming to dinner?" prompted a sigh.

"And who is my neighbor?"

As he became a juvenile court commissioner, judge, Big Brother and active Christian

layperson, Utter grew increasingly frustrated with theological silo building. He

wishes more people would cut to the chase and just read and heed Christ's words.

The Parable of the Good Samaritan early on became his North Star. In Luke, Chapter

10 verses 25-37, we encounter a lawyer who decides to see if Jesus is fast on his

feet:

"Teacher," he asked, "what must I do to inherit eternal life?"

"What is written in the Law?" Jesus replied. "How do you read it?"

The lawyer answered: " 'Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all

your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind. And, 'Love your neighbor

as yourself.' "

"Exactly," Jesus replied. "Do this and you will live."

But the lawyer probed for a definition: "And who is my 'neighbor'?"

Jesus told the story of a man who was set upon by robbers while traveling from Jerusalem

to Jericho. They beat him, took his clothes and left him half dead and naked alongside

the road. A priest happened by, but when he saw the hapless victim, he moved to

the other side of the road. Shortly thereafter, a Levite did likewise. At last,

a Samaritan took pity on the victim, bandaging and salving his wounds. Then he put

the man on his own donkey, took him to an inn and made him as comfortable as possible.

The next morning, he gave the innkeeper two silver coins. "Look after him," the

Samaritan said, "and when I return I will reimburse you for any extra expenses you

may have incurred."

"So," Jesus asked the lawyer, "which of these three do you think was a neighbor

to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?"

"The one who had mercy on him," said the lawyer.

"Go and do likewise," Jesus advised.

I simply have to face a world where I know unjust things occur. I know that God is love, and I rebel against the injustice I see in this world.

Utter fervently believes that Jesus is emphasizing that compassion should be for

all people, and that fulfilling the spirit of the law is just as important as fulfilling

the letter of the law. Moreover, your "neighbor" isn't just the guy next door; it's

everyone in the family of man.

Juvenile Court was "a real eye-opener" for Utter, who had "no realization of the

extent of deprivation children faced in our society." It was bad then, and it's

dramatically worse today, the judge says. "I probably heard at least 3,000 cases

each year, and I came to growing realization that love is the absolute cornerstone

of the meaning of family life. Parents can provide everything from material and

educational standpoints, but if children have not experienced love and an appreciation

of their self-worth, they have nothing to build on." More importantly, he came to

see that when children get into trouble society writes them off at its peril. Given

the right intervention, a second chance, even a third chance, problem kids can become

responsible adults with children of their own who won't be neglected. Neglect begets

neglect, Utter emphasizes.

"I have seen things which I don't understand and which have torn my heart apart.

Children who are abused sexually and physically, who are involved in drugs and prostitution.

These would leave anybody questioning who sees this time and time again. I simply

have to face a world where I know unjust things occur. I know that God is love,

and I rebel against the injustice I see in this world.

"The most difficult thing for me during those years in Juvenile Court was to see

marvelous human beings who I knew could make it if they had just a little more help

from others - a few hours of a person's day, the impetus for a little more education.

I can only say, 'God, I'll do a little bit. I'll do as much as I can and then leave

it to You to provide the answers.' "

At the next level, there were even more terrible questions and elusive answers.

"To Die Is Not Enough"

Robert F. Utter's scrapbook.

Robert F. Utter's scrapbook.

After five years as a Juvenile Court commissioner, 34-year-old Robert Utter had

developed a reputation as a bright and thoughtful judge and civic activist. Besides

his work with Big Brothers, in 1964 he was the co-founder and president of Job Therapy

Inc., a nationally recognized vocational and mentoring program for convicts and

those on parole. Also active in the YMCA and PTA, he was a deacon in the Seattle

First Baptist Church. The Jaycees named him "Seattle's Most Outstanding Young Man"

in 1964. Judges, law enforcement officers and other admirers urged him to run for

the King County Superior Court bench. There were two other candidates, but Utter

campaigned tirelessly, striving for "a knockout punch" in the primary. He had given

more than 200 talks to PTAs and other groups in the past year, and it paid off.

He took fully 60 percent of the vote.

Shortly after his re-election, without opposition, in 1968 Judge Utter met a murderer

who changed his life and whose life he would change. To understand why Robert Utter

feels so passionately that the death penalty is just plain wrong you need to know

about Don Anthony White.

Don Anthony White was a 22-year-old black man who'd been in and out of reform school,

mental institutions and jail. On Christmas Eve, 1959, he stabbed to death a black

longshoreman when they quarreled while drinking. White got the "weird shakes" and

"just went into a mad rage." Afterward, he said he "went wandering" and found himself

in the laundry room of a housing project where as a child he used to take refuge

for hours in the clothes dryers. ("It seemed like nothing could get to me in there.")

As he started to leave, a gray-haired woman "banged the door by the dryers." In

a flash, he crumpled her with a savage blow. Then he raped her and left her dying.

In truth, he'd attacked the woman first and the man some 15 hours later. Clearly

in one of his "fogs," White confessed to the killings without benefit of legal counsel.

He told his parole officer, "I should've been in the bughouse a long time ago. …

I get wound up and reach a point where something has to happen …something violent…

bam!" He slammed the table with his fist. "If I get a lawyer and he tries to get

this reduced from 'murder first' to 'murder second' I'm not going to let him. It

probably would be better if I did drop off the end of that rope."

White had been raised from infancy by an emotionally disturbed foster mother. She

told bizarre, rambling stories about how she had acquired the child on a visit to

Kansas. Her ex-husband testified that when she was angry with Don she would tell

him he'd been thrown in the garbage and "nobody didn't want him." Sometimes "when

she would get mad, she would hold his head down between her legs" and whip him with

the cord to the iron. Don was often so enraged over the whippings and other abuse

that his foster sister thought he "could've murdered her or something. His eyes

would get real funny lookin' …bright red … like a person who was outta their mind."

Don attempted suicide at the age of 5. "That damned garbage can" was seared into

his brain. "Oh, God, that used to bug me!" he told a court-appointed psychiatrist.

A perpetual truant and runaway since the age of 7, Don Anthony White was extraordinarily

bright, which other children resented. He told counselors that he had endured non-stop

racism at school and the children's mental health center, where he was the only

black child. He fled the classroom one day, sobbing that he hated being called "nigger."

At home, he'd go into a psychotic, trancelike state and "get the awfullest headaches,"

his foster mother said. Then he'd break the furniture and threaten to burn the house

down. In 1951, the 14-year-old was diagnosed with childhood schizophrenia that was

rapidly progressing into the psychotic symptoms seen in adult sufferers. At the

rate he was descending into madness, they said he was bound to seriously injure

or kill someone. When they first sat side by side, one of his court-appointed attorneys

said he was afraid his client might kill him. White soon realized, however, that

someone actually genuinely cared about him. They were trying to save his life.

The attorneys worked tirelessly to demonstrate that he should be committed to an

institution for the criminally insane, but on May 27, 1960, an all-white jury found

him guilty of the murders and recommended that he be put to death.

The next eight years were punctuated with despair, resignation and hope. White's

attorneys never gave up. In the King County Jail, then on Death Row at Walla Walla,

Don's other frequent visitors included Quakers, nuns and priests - even the Roman

Catholic bishop of Spokane. A librarian saw to it that he received books "to challenge

his capable mind." Investigative reporters took up the cause of mentally ill inmates.

Among them was Donald Delano Wright, who wrote a prize-winning series on the death

penalty for The Seattle Times.

By 1963, the murderer had made remarkable progress. He stunned the judge who was

about to sign his death warrant by thanking him for his courtesy. White said his

two lawyers "were the greatest" and praised the prosecutor, who was "a gentleman

all the way." White said: "I abhor the nature of the crime that I am here for, yet

I hope that other people who commit similar crimes will benefit from it somehow,

that the death penalty will pass from our scene and that we will all understand

a crime of this nature a little bit better." The judge was stunned at the transformation.

He called it "a magnificent thing - one of the finest statements I have ever heard

in open court."

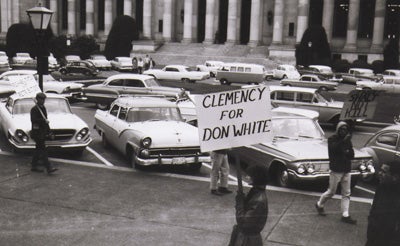

Death penalty opponents picket at the steps of the Capitol, urging Governor Al Rosellini to grant Don Anthony White clemency.

Death penalty opponents picket at the steps of the Capitol, urging Governor Al Rosellini to grant Don Anthony White clemency.

Don Anthony White found himself, God and, in time, a full measure of sanity. The

state still wanted him dead. On the eve of Palm Sunday, 1964, with White's date

with the gallows just days away, Joan Baez, the famous folk singer, and a dozen

pickets staged an all-night vigil in front of the Capitol at Olympia. Inside, Gov.

Al Rosellini was mulling a swarm of pleas for clemency. He invited Baez and some

of the other death penalty protesters into his office. Rosellini's Republican opponent

in his upcoming bid for re-election, State Rep. Dan Evans of Seattle, believed the

death penalty was "barbaric" and had "not proven to be a deterrent to crime." Finally,

Gov. Rosellini granted a 30-day stay of execution.

The appeals and petitions dragged on. Evans went on to defeat Rosellini and fought

a relentless but losing battle against capital punishment during his unprecedented

three terms as governor.

Months became years. The State Supreme Court repeatedly turned a deaf ear. Undeterred,

White's lawyers kept advancing the key issue that he had been interrogated by police

without benefit of counsel at a time when he was emotionally defenseless.

Then, on Good Friday, 1966, Don Anthony White's conviction was overturned by a federal

judge in Boise. Resolute, prosecutors filed an appeal with the U.S. 9th Circuit

Court in San Francisco. In 1967, the appellate court granted White a new trial in

King County Superior Court. The judge was to be Robert F. Utter, whose work with

young offenders and strong commitment to rehabilitation seemed heaven sent for Don

Anthony White. The young judge also treated all before him with courtesy.

Don Anthony White, flanked by his lawyers,

James C. Young, left, and David A. Weyer in 1963.

Don Anthony White, flanked by his lawyers,

James C. Young, left, and David A. Weyer in 1963.

Courtesy Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Hopes sagged at the defense table when Utter promptly sided with the prosecution,

ruling that White's confession and the tapes of his interrogations could be admitted

into evidence. "A new trial is not a new case," the judge said. Crucially, however,

Utter would not let the jury see an inflammatory morgue photo of the woman White

had killed. Her scalp had been shaved for the autopsy, and the first jury had been

horrified by the image. Utter also allowed a defense psychiatrist to testify that

White was out of his mind when he committed the murders. The rape, the psychiatrist

added, was not of a brutal nature and "may actually have represented some kind of

a primitive, infantile attempt to have a sexual relationship with a mother-person…"

The defendant told the jury he was not yet fully safe to be at large - but what

good would killing him do when he might yet do some good himself? White was making

certain that his own attorneys could not fashion a defense based on the assertion

that he was insane in 1959 but now should be set free. Further, during his first

trial, a psychiatrist testified that the killer was irreversibly psychotic. In the

second trial, Utter notes, White showed no signs of psychosis, "one more example

of our inability to judge with finality that there is no hope of changing a person."

In the summer of 1968, the King County jury found White guilty of both murders,

but rejected the death penalty. The next day, Judge Utter asked White if he had

anything to say. He did: "Martin Luther King said that there is a mountaintop. I

have been clawing to get there for a long time, and I won't stop now…"

The prosecution urged Utter to recommend to the State Parole Board that White's

minimum term be set at life, without possibility of parole. "The judge flatly refused

to interfere with the Parole Board's discretion," Donald Delano Wright wrote in

his riveting book about the case, To Die Is Not Enough.

"The transformation in Don Anthony White over the course of those eight years was

truly remarkable," Judge Utter wrote. "He had graduated from high school and Walla

Walla Community College in prison, studied architecture and drafting through correspondence

courses and became an accomplished painter, able to portray with brushes and canvas

many of the conflicts that tormented his soul."

White's brother, Karl, an outreach ministries pastor in Georgia, says that "with

the discovery that people actually cared about him as a person, he finally really

started coming out of the psychosis and finding himself."

With time off for good behavior and the support of Gov. Evans, Don Anthony White,

Inmate No. 117121, was sent to a work-release program at Western State Hospital

in Steilacoom in 1976. The rest of this story, unfortunately, lacks an entirely

happy ending.

White began working for the Tacoma Urban League and was a popular employee. In 1979,

however, some of the old demons returned. Don was in "emotional turmoil" when he

was subpoenaed as a defense witness in a death penalty case. Asked to describe what

it was like to live in the shadow of death, he told of hearing the trapdoor spring

open as his nextdoor neighbor on Death Row was hanged. To relive those moments "was

a very harrowing experience for someone who was locked up for so long," an Urban

League social services director told reporters.

Don failed to return to the halfway house and was reported to police as AWOL the

next morning. "Everybody - his sponsor, his fiancée, all the people who are supportive

of him, are all just shocked," the state work-release supervisor said.

White told his brother he had to get away and took off on what he called "a month-long

vacation" across the country. Then he turned himself in and was sentenced to five

more years in prison for escape. He ended up at the correctional center at Vacaville,

Calif., where he helped with the orientation of new correctional officers and prisoners.

Don did his last two years back in Washington State. Paroled again in 1987, he left

Tacoma to become director of the Abolition of the Death Penalty Project for the

American Friends Service Committee in Oakland, Calif. He appeared on the Oprah Winfrey

show and spoke frequently before church and civic organizations. He often appeared

as a witness in death penalty cases. That part was still the hardest. Being in court

"always brought back a lot of memories from his trial," his brother recalls. "He

used to tell me, 'I'm alive, well and enduring.' "

...at no point in the life of a human being are we wise enough to say a person is beyond redemption.

There was more to endure. He was badly injured by a mugger in Oakland in 1991. Decades

of chain-smoking, stress and diabetes also took their toll. Don Anthony White died

in Oakland on Feb. 23, 1995, after suffering several strokes, but the Rev. White

says his brother had happily married and was a productive, loving person. He and

Justice Utter say that Don's life story stands as one of the most compelling cautionary

tales against capital punishment. "It makes no sense," Don Anthony White told reporters

not long before his death. "It doesn't bring anybody back."

"Judge Utter, in the words of one of Don's attorneys, 'permitted introduction of

evidence covering the broadest spectrum of rehabilitation,' " Karl White recalls

today. "He took a stand for equal justice. For a young judge to go up against the

system was really impressive, not even considering the racial climate at the time."

Utter's actions "caused me to do a lot in the ministry, especially with young African-Americans

and Latinos … working with youth at risk. His conclusion that the death penalty

is not fair, not a deterrent and, in his words, an 'unjust law,' " amounts to an

indictment of a prison system "that merely warehouses people and does not rehabilitate,"

Pastor White has written.

The moral of the Don Anthony White story is that "at no point in the life of a human

being are we wise enough to say a person is beyond redemption," Utter believes,

adding that a life sentence without the possibility of parole protects society just

as well.

A new appeal

In 1968, Gov. Evans, impressed by Judge Utter's track record on and off the bench,

named him to the newly-authorized Washington Court of Appeals. Utter ran unopposed

for a full six-year term the following year.

Utter kept pushing for prison reform and community-based counseling and detention

facilities that could serve as workrelease centers. "The failure to provide realistic,

post-institutional support for men until they can be reintegrated back into the

community would seem to practically guarantee they must return to crime to provide

the basic necessities of food, clothing and shelter," he wrote during that era.

He was still active in Job Therapy Inc. and also outspoken on victims' rights. "Dangerous

offenders must be removed from the streets," he told the Young Lawyers group in

King County, also emphasizing that 85 percent of the men in prison are not dangerous

offenders. If society thought it was making things better by warehousing men in

lonely institutions, with little opportunity for substance abuse counseling, education

or vocational training, Utter said it was a false sense of security. "We have to

realize that we are dealing not only with ideals, but with human beings." The judge

is an admirer of former governor Booth Gardner, who shares his commitment to helping

disadvantaged youth. "Booth put it so well when he always reminded the taxpayers

that when it came to investing in programs to help kids, 'You can pay me now or

you can pay me later, and later is going to be a lot more expensive in more ways

than one.' "

"Our current penal system is an offense-oriented system, not an offender-oriented

system, and the maximum sentence is based on the offense committed rather than on

the capacity of the offender for change," Judge Utter said in a 1970 speech. He

urged the Legislature to establish a "dangerous offender category" in the criminal

code to deal with the 15 percent who definitely "must be separated from society

for safety reasons."

Kindred souls

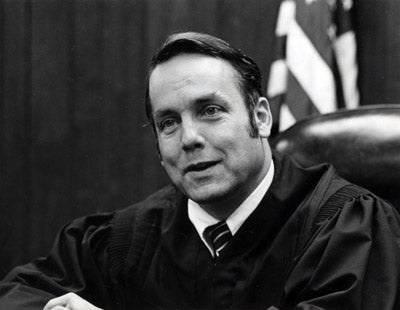

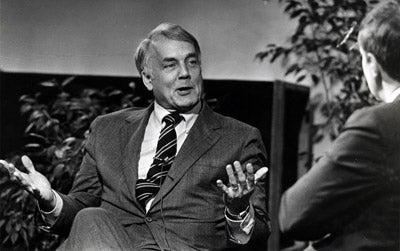

Justice Utter on the Washington Supreme

Court, 1972.

Justice Utter on the Washington Supreme

Court, 1972.

In December of 1971, Justice Morell E. Sharp, who'd been on and off the State Supreme

Court for a topsy-turvy total of 13 months, resigned to accept a Nixon appointment

to the Federal District Court. Gov. Evans didn't need to sleep on that opportunity.

His pick was Robert F. Utter, a judge after his own heart. Evans and Utter were

classic progressive reformers in the Teddy Roosevelt mold. The former Eagle Scout

and the liberal Baptist both opposed the death penalty, cared deeply about the environment

and social services and strongly advocated youth programs.

Utter took the oath on Dec. 20, 1971. He was 41, having made the leap from Juvenile

Court to the state's court of last resort in 12 years.

He has been so closely identified with his opposition to the death penalty that

his diverse body of jurisprudence is often overlooked. He has defended free speech

and religious liberty and ruled curfew ordinances unconstitutional. Utter was also

a vigorous proponent of forcing the state to fulfill its "paramount duty" to fund

basic education. The "special levy roulette" system of the 1970s improperly forced

the school districts to rely heavily on local funding for basic programs, Utter

maintained. "As such, it violates the constitutional requirement that the state

itself make ample provision for the school system. This is not to say that special

levies cannot be used, but only that it is impermissible that they be relied upon

to meet the minimum needs of the schools." Narrowly rebuffed in 1974, his side regrouped

to a 6-3 victory in 1978. "The Constitution meant what it said," Utter emphasizes.

Other key cases during his 23 years on the high court included carrying the day

in a split decision that struck down a "tort reform" law that would have capped

the recovery of general damages in personal injury cases. In 1983 and 1984, he waded

into one of the state's most celebrated snafus, the collapse of the Washington Public

Power Supply System's nuclear power plant projects. WPPSS - pronounced "Whoops!"

by irate ratepayers - also left thousands of bondholders in the lurch. They found

no relief from the high court majority. Utter begged to differ, arguing that the

cases couldn't be resolved without a trial to weigh the unresolved questions of

fact. "The parties should win or lose in the courtroom," he wrote. "It doesn't matter

what the public pressures are." He told the State Trial Lawyers' bulletin that those

two dissents "tell as much about my judicial philosophy as any case."

Utter was developing a national reputation as a scholarly judge. But it wasn't all

smooth sailing.

"The Power of the Holy"

Utter finds solace at sea.

Utter finds solace at sea.

Another of the epiphanies in Utter's life occurred in 1976 during the 2,500-mile

Victoria-to-Maui sailboat race, his first event as a skipper on the open ocean.

"I was not quite certain what I would find," he wrote later, "and suspected that

Columbus's crew was correct that the world was indeed flat, with a great waterfall

at the end over which all intrepid mariners would fall."

The legendary mountain climber Willi Unsoeld, a good friend and neighbor on Cooper

Point in Olympia, often told the Utters that he had experienced many more spiritual

moments "among the bare austerities of God's high places" than in churches, chapels

and synagogues. Unsoeld, who had a doctorate in theology and philosophy, believed

that our fear of "The Power of the Holy" is actually the beginning of wisdom. "Willi

found evidence of that power in the unscaled mountains of this world and described

it as the type of power that convinced us we were no longer in charge of our destiny,"

Utter recalls. Pointing to his bad knees, the judge jokes, "even the small bit of

climbing I did convinced me that there had to be other ways to find the presence

of God that were not quite as terrifying" as the North Face of Mount Everest. "Little

did I know that my love of sailing would lead to similar experiences."

When the 41-foot Nerita sailed out the Straits of Juan de Fuca, the novice skipper

took a fleeting glance at the last land he'd see for days, surveyed the largely

green crew of seven he was now responsible for and realized that "there are no large

boats on the ocean." Utter was at the helm "one stormy morning, just as dawn broke,

steering down towering seas with the spinnaker set, catapulting down the face of

one wave after another." The judge began to sing at the top of his lungs Sunday

School hymns he thought he had long since forgotten. One was the rousing old gospel

tune, "There is a Wideness in God's Mercy":

There's a wideness in God's mercy,

Like the wideness of the sea;

There's a kindness in His justice,

Which is more than liberty.

There is no place where earth's sorrows

Are more felt than up in heaven;

There is no place where earth's failings

Have such kindly judgment given.

For the love of God is broader

Than the measure of our mind;

And the heart of the Eternal

Is most wonderfully kind.

"There is a Wideness in God's Mercy" contains several messages, Utter realized -

the admonition to be kind, the promise of reconciliation and the reminder that our

sins are as painful to God as they are to us. "Later experiences in dealing with

children and adults in court convinced me that the overwhelming Power of the Holy

is found not only in nature but in the lives of his creation and that we can never

be certain of what the effect of that power will be unless we give it an opportunity

to manifest itself," Utter wrote.

"The Power of the Holy" came into even sharper focus for the judge in the 1980s

when he met James M. Houston, the Oxford don who was a revered professor at Regent

College, the international graduate school of Christian Studies in Vancouver, B.C.

Houston's essay on "Living in a Suffering World," touched Utter's heart and soul.

"The book of Job teaches that to live in a meaningful world one needs to cultivate

proper attitudes rather than depend upon simple answers," Houston wrote. "Relating

to God is more profound than knowing about God."

For the record, Utter and his crew didn't win that race, but they were a commendable

third in their class, and the judge won a prize more coveted than any silver cup:

A new sense of self-confidence and the realization that God works in mysterious

ways.

In Utter's second race, the sailboat skippered by his partner, Carter Kerr, was

first in its class and second overall. "It was spectacular!" Utter recalls, sipping

hot chocolate in the cabin of his latest sailboat on a sparkling March day, with

the snowcapped Olympics as a backdrop for Budd Inlet.

The Utters on the Tacita in the late

1960s. The kids are, from left, Kim, John and Kirk.

The Utters on the Tacita in the late

1960s. The kids are, from left, Kim, John and Kirk.

Sailing has been a family affair for the Utters from the time their children were

in diapers. Kim was born in 1957; Kirk in 1959 and John in 1965. Kirk, in particular,

shares his father's fascination with the sea and is rated among the top 10 sailboat

crew members in the Pacific Northwest. In the 7th grade, his mother also proudly

notes, he had a key role in Seattle Opera's production of "Peter Pan," soaring above

the stage on guy-wires. Kirk Utter graduated from the University of Puget Sound

and now works in the satellite communication industry. His brother John, a Whitman

College graduate, is a fine guitarist, composer and singer. He had a pop music band

called Bounce the Ocean. John has done Web design for the state, including a site

to boost the skills of women returning to the workforce. Kim Utter is also wonderfully

musical, a pianist and singer. Lately, her recitals feature some Bach, and she enjoys

the singing in the Gloria Dei choir. She loves her new electronic piano. Sometimes

on the sailboat, they'd all sing old sea chanteys. Bob has studied guitar "without

much success," but he loves music and is a fan of Andres Segovia, Eric Clapton and

Robert Johnson, the legendary Delta Blues guitarist who claimed he sold his soul

"at the crossroads" to be able to play like the Devil.

Bob and Betty Utter now dote on four grandchildren.

The defining moment

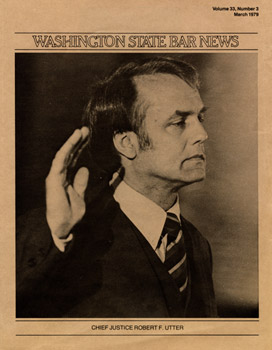

Utter takes the oath as chief justice

in 1979.

Utter takes the oath as chief justice

in 1979.

Utter served as chief justice of the Supreme Court from 1979 to 1981, a time when

Washington State's new death penalty legislation was tested in both the high court

and the federal courts. Utter was also tested at the ballot box. The Kitsap County

prosecutor, Dan Clem, was an energetic challenger in 1980. Clem asserted that Utter

would go off "on a state constitutional law binge" whenever he disliked what the

U.S. Supreme Court was up to.

Utter won re-election in a landslide, and concluded with satisfaction that while

the voters might not agree with him, they respected his integrity and independence.

His platform, in fact, had always been "that if I think you are right, and no one

else agrees with you, you can be certain I will still vote for you."

From 1981 to his resignation in 1995, Utter and his colleagues heard 25 cases where

the death penalty was imposed by a lower court. The Supreme Court upheld the death

penalty in all 25, with Utter dissenting 24 times. He emphasized repeatedly that

"the fatal flaw" was the lack of proportionality. In 1984, he noted in dissent that

one of the defendants in Seattle's "Wah Mee Massacre" of 13 people faced the death

penalty while his two accomplices did not. "The Washington capital punishment scheme

is applied arbitrarily, without pattern or meaningful standards, and therefore violates

the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution,"

Utter wrote.

The one case in which he concurred was the last he heard as a member of the court,

and the majority adopted his opinion, which set aside the death penalty on procedural

grounds.

"Although the action of the federal courts in overturning our cases was encouraging,

I began to question whether I could continue to function in a legal system that

imposed the death penalty." In 1993, his doubts became even stronger after the state

carried out its first execution in 25 years.

The defining moment in his decision to resign from the Supreme Court came in the

fall of 1994 when he read Hitler's Justice: The Courts of the Third Reich,

by Ingo Müller, a German lawyer and law professor. A best-seller in Germany, the

book details the perversion of justice under Nazism. Winston Churchill once described

Hitler as "a maniac of ferocious genius, the repository and expression of the most

virulent hatreds that have ever corroded the human breast. …" All that was played

out in the Nazi courts, as ancient anti-Semitic hatreds and "Aryan" mumbo-jumbo

made a murderous mockery of the rule of law.

Utter read the book practically in one sitting. Then he couldn't sleep. "Müller

chronicles how the entire legal system, including judges, lawyers and lawmakers,

was co-opted to serve a lawless regime with the corresponding death of the rule

of law and its legal institutions," Utter wrote in Unjust Laws, a widely read 1997

essay in the Cardozo Law Review. German justices, lawyers and law school professors

"overwhelmingly openly acquiesced" to Hitler's seizure of power in 1933, "then enthusiastically

collaborated in the worst excesses" of a regime that ignited a global war and summarily

shipped millions of Jews, together with Gypsies, Jehovah's Witnesses, gays, annoying

Lutherans and assorted other "enemies of the Reich," to concentration camps where

the ovens glowed 24/7. Meantime, the "mentally deficient" were liquidated to protect

and enhance the Reich's precious gene-pool while judges looked the other way.

"What was particularly striking," Utter wrote, was Müller's "short chapter on 'Resistance

from the Bench' - short because there was little resistance. In fact, he told of

only two non-Jewish judges who actively protested the actions of the Nazi government

by resigning."

Worn down by dissents that went unheeded, "I could see myself, my own views, becoming

less vigorous," Utter said. "I became concerned that if I stayed in the system …

that this would happen to me."

The judge who had always strived to disagree without being disagreeable took pains

to emphasize he wasn't suggesting that America as a nation or his colleagues on

the court were on the slippery slope to fascism. However, he said he believed too

many people in places high and low were turning a deaf ear to the injustice of Death

Row amid the cry to "get tough on crime."

His resignation was effective April 24, 1995. After nearly 24 years in the trenches,

no one could call him a quitter or suggest that he wasn't putting his money where

his heart was. He was walking away from a $100,000-a-year salary as a matter of

conscience. Utter kept recalling the words of Don Anthony White, who told his attorneys

that "dying was not enough." He was prepared to go the long extra mile to help society

come to grips with what happens when children are made to feel like garbage.

If conscience is in fact a sacred sanctuary where God alone may enter as judge,

then I believe my internal court reached the proper decision.

"The death penalty squanders the legal and moral resources of our nation in the

futile effort to accommodate fundamental tensions that make any civilized administration

of the death penalty impossible," Utter wrote in the Cardozo Law Review essay about

his decision.

"… Society cannot accept the possibility of executing wrongfully convicted people.

… By remaining a part of that system I was implying that it could be made workable.

… The injustice that I perceived … became a growing burden.

"I recognize there are those who conclude otherwise. While I respect their views,

the struggle is a personal one for all involved, and my conclusion is uniquely my

own. If conscience is in fact a sacred sanctuary where God alone may enter as judge,

then I believe my internal court reached the proper decision."

The resignation received front-page coverage around the Northwest. Even death penalty

supporters said they respected Utter's integrity. Two of his allies against capital

punishment, Justices Charles Z. Smith and James Dolliver, said he would be sorely

missed. "Someday," Dolliver wrote, "we will eliminate the death penalty and be saved

from cries of vengeance, revenge or justice and thus become a more truly civilized

community of citizens."

"He has been a voice for reason and justice and the court will simply not be the

same without him," said Chief Justice Barbara Durham, who disagreed with Utter on

capital punishment. Seattle Post-Intelligencer columnist Charles Dunsire regretted

"the loss to state service of an exceptionally fine judicial mind and an individual

whose legal opinions and actions reflect admirable humanitarian qualities." King

County Prosecutor Norm Maleng noted that "the death penalty has been upheld by the

U.S. Supreme Court and it is the law of the land, but I can respect the decision

he has made."

In 1996, Utter was a panelist on a New York City Bar Association symposium entitled

"What Role Should Morality Play in Judging?" Other panelists, including fellow judges

and law professors, noted that his decision to resign over the death penalty italicized

the issue of conscience "in a dramatic and forceful way … and may very well have

changed the terms of debate" on capital punishment in America. A lively discussion

ensued: What constitutes a violation of a judge's constitutional oath? What are

the bounds of civil disobedience? If you don't "play by the rules," doesn't that

jeopardize the integrity of jurisprudence? After all, "if judges choose to not go

along with precedent in one case, it is hard to see why they cannot do so in all

the rest," a panelist suggested.

Utter responded that a judge is bound by oath of office to faithfully and impartially

try the case at hand. "I have never considered opposing this principle. I may have

occasionally interpreted statutes in ways the federal courts later disagreed with

where the meaning was unclear, but I have never considered it judicial lying. I

think the key to the system is the judge's adherence to that oath. In my case, that

was to follow the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution and laws

of the State of Washington."

The popular humorist, Finley Peter Dunne, famously declared in 1896 that "even the

Supreme Court follows the election returns." Utter turned that notion on its head.

He told the panel that 80 percent of the people in his state favored the death penalty,

yet he was undefeated in five statewide elections.

Trust eroded?

Despite his record of success at the ballot box, Utter is flatly opposed to judges

being forced to become politicians to keep their seats. He has long maintained that

requiring judges to stand for election is an "assault on the integrity of the entire

judicial system." Ethics, the pitfalls of making campaign promises and raising a

war chest add up to a trifecta of reasons why a merit selection process should be

adopted, he believes.

Utter advocates the establishment of a nonpartisan commission, including non-lawyers.

It would carefully evaluate candidates and submit its top three to the governor

for appointment. He is appalled at the hundreds of thousands of dollars now being

raised and spent to elect Supreme Court justices in Washington State and the bare-knuckle

nature of recent campaigns. When judges have to go out, hat in hand, and raise money

for TV sound bites from lawyers who end up appearing before them in court - not

to mention the major lobbying groups who bankroll campaigns - he believes the system

is compromised and public trust eroded.

Utter was outspoken on the issue in the 1990s during his term as chairman of the

American Judicature Society, which has long advocated for the merit selection and

retention of judges and the effective administration of justice.

Speaking of which, Utter recalls that when the voters approved the new Court of

Appeals in 1968, the ballot issue also contained a proviso that the State Supreme

Court could be reduced by two to a total of seven members. "But the voters promptly

forgot about that." He still believes a smaller Supreme Court would be more efficient.

"I wrote no dissents when I was on the Court of Appeals. With three members you

could focus on the issues and communicate better," he noted in 1999 on the occasion

of the appellate court's 30th anniversary. "I wrote a few when I was on the Supreme

Court," Utter added with a smile.

The teacher

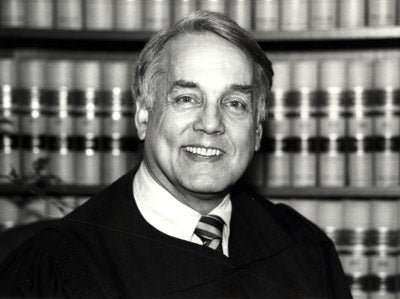

Justice Utter on the Washington Supreme

Court, 1992.

Justice Utter on the Washington Supreme

Court, 1992.

In the 1990s, Justice Utter taught a popular course on state constitutional law

at the University of Puget Sound School of Law. In 2002, he teamed up with his friend

Hugh D. Spitzer, a lawyer and University of Washington Law School professor, to

complete a book he had been working on for several years. The result was

The Washington State Constitution (Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-27464-9),

a definitive reference guide.

"One amazing thing about Bob," Spitzer says, "is that while he was on the State

Supreme Court, working with his colleagues, writing opinions and dealing with administrative

matters, he managed to put in the time and the intellectual rigor to write cutting-edge

law review articles on state constitutional law topics - lots of them, and all very

thoughtful and analytically deep. These pieces gained instant recognition nationally,

and for good reason."

Spitzer says Utter was also "a great tactician." Each case is assigned randomly

to a Washington Supreme Court justice, who then drafts an opinion. "When Utter was

assigned a case … he was a master at piecing together a majority. When necessary,

he would shift the issue in the case to avoid losing the right to compose that majority

opinion and to avoid seeing the law develop in a direction that he saw as being

harmful on a long-term basis. When he 'lost' a case and was in the dissent, he was

a master at reconfiguring and reinterpreting the majority opinion when he had the

opportunity … in a later opinion involving a related legal issue.

"It's also important to note that Bob Utter is one of those people who treats every

other human being with precisely the same high level of respect," Spitzer adds.

"His professional success and recognition never went to his head. He's obviously

comfortable enough with who he is that he doesn't have to bulk up his ego at the

expense of others. My late aunt was a social worker in the Juvenile Court 45 years

ago when Utter was a young Superior Court judge. She always told me what an incredibly

nice person he was to staff members and how much respect he showed to kids who appeared

before him. I discovered the same thing when I was a young lawyer/law teacher and

beginning research on the State Constitution."

Washington Supreme Court Justice Richard B. Sanders says Utter's "most important

intellectual achievement is that effort to popularize the State Constitution and

give it real meaning and application."

"When I went to law school at the UW in the 1960s," Sanders says, "there wasn't

even a class on state constitutional law. Then, in the 1980s, Justice Utter authored

an article for the UPS Law Review that served as a template on how to construe our

State Constitution. This is important work, because in terms of civil liberties

the Federal Constitution sets a floor for individual liberties, but not a ceiling.

This gives the states leeway to provide stronger protections."

Justice Charles W. Johnson agrees: "Utter's development of an independent interpretation

of the State Constitution was probably as strong an influence on this court as could

have been achieved by any individual. It was not a philosophy embraced by everyone

because it's not a comfortable philosophy. But the way Bob explained it in his writing

was persuasive. As lawyers and judges, we're most comfortable with the federal Constitution.

That's what we're taught in law school. We're not exposed to the State Constitution

if we're practicing law or judging at the lower court level.

Utter's development of an independent interpretation of the State Constitution was

probably as strong an influence on this court as could have been achieved by any

individual.

"Primarily," Johnson adds, "the issues revolve around the privacy provisions - search-and-seizure

jurisprudence under Article 1, Section 7, as compared to the 4th Amendment. The

language is entirely different, which is absolutely unique and that left us with

the challenge of determining 'Do these words have independent meaning?' Some said

'no' and some said 'yes,' and that was the debate. What Bob Utter did before I came

on the court was develop a language, or at least a foundation of the principles

that explained not only what these words meant to the drafters but how they should

be applied. And it made sense. … The door was not closed to the state constitutional

interpretation because Bob Utter had kept it open."

William L. Downing, a King County Superior Court judge who spent 11 years as a prosecutor,

was "aghast" at his earliest encounters with Justice Utter. "In the early 1980's,

I was a naïve young deputy prosecuting attorney and I wanted to know just who was

this State Supreme Court justice who thought he could overrule the United States

Supreme Court? The Supreme Court of Warren Burger was eagerly loosening the restrictions

that had been placed on police and prosecutors during the era of Chief Justice Earl

Warren, but some of the states were refusing to go along. Justice Utter seemed to

be gaily leading this revolutionary charge.

"Initially outraged, I took a closer look. What I found soon turned my head around.

First, I discovered there was nothing revolutionary afoot," Downing says. "The rules

being articulated by Bob Utter were entirely sensible ones for police, prosecutors

and trial judges to follow. In fact, if anything was radical, it was the sudden

federal cutbacks. I also found there was an undeniably principled basis for what

was being done. Justice Utter made sure that adherence to the State Constitution

as a protective layer for individual liberties was an intellectually honest approach,

with history and logic behind it. These discoveries turned me from a critic into

a staunch supporter of Justice Utter and our Washington Supreme Court."

Downing was to see another side of Utter in the early 1990s when as a parent and

a judge he became active in Youth & Government. "As a proud graduate of this

YMCA program, Utter's first-hand awareness of its value made him a passionate driving

force in spreading its reach. The young people of Washington today continue to be

enriched by his decades of contributions.

"Over the years, I have seen Bob Utter in many settings and he has graced them all.

His presence made the courtroom a more dignified and intellectually stimulating

place," Downing says. "I have observed him interacting with young people, including

my own son. His manner and his obvious interest have helped so many of them move

closer to realizing their potential. And, from a distance, I have looked on as he

has gone global with his always principled and always persuasive message."

A traveling man

"Going global" is putting it mildly. Utter was an active volunteer with international

judicial outreach programs during his later years on the high court, and when he

left the bench he seemed to be everywhere. The fall of 1991 found him lecturing

at a judges' academy in Moscow shortly after the failed coup against Boris Yeltsin's

progressive reforms. The Communist monolith that was the Soviet Union collapsed

just a few months later. "It was one of the most interesting times of my life,"

Utter says. "All was in flux about what form the post-Soviet world would take."

In 1992, the Dali Lama's legal adviser called Utter to get some advice on how to

draft the criminal law code for the Tibetan Government in Exile. Utter emphasized

dispute resolution and rehabilitation.

The Utters and other members of the

delegation outside a yurt in Kazakhstan in 1992. Made of felt, yurts are the traditional

nomadic dwelling of Kazakhstan.

The Utters and other members of the

delegation outside a yurt in Kazakhstan in 1992. Made of felt, yurts are the traditional

nomadic dwelling of Kazakhstan.

The Utters have made as many as five trips abroad in one year to promote the rule

of law and human rights in new and emerging democracies. As a volunteer with the

American Bar Association's Central European & Eurasian Law Initiative - "CEELI"

for short - Utter has shared his decades of judicial experience and knowledge of

constitutional law with judges from some 20 countries, including the former Soviet

states of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and assorted other "stans," which he

can pronounce like a native. He tells moving stories of brave men and women putting

their careers - sometimes their very lives - on the line in defense of an independent

judiciary. One formerly embattled judge told Utter that he had no choice but to

stand up to the KGB because "in a nation of slaves, the revolt of one slave is significant."

Betty Utter invariably ends up teaching English on these trips. There's not much

time for sightseeing. The Utters aren't disappointed. They say they've learned more

from people-to-people interaction in huts and village halls than on any tour bus.

Their prized souvenirs include humble but beautiful rugs, folk arts and crafts.

Betty and Bob Utter in the hills of

Kazakhstan.

Betty and Bob Utter in the hills of

Kazakhstan.

Bob has taught in Latvia, Serbia, Armenia, Moldova, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic

and both Outer and Inner Mongolia, where he led a People to People group in 1989,

a time when there had been few outside visitors. "We had an opportunity to see how

their ancient process of neighborhood councils for dispute resolution worked."

In Albania in the 1990s, he joined several other American judges and lawyers in

a series of seminars and lectures. The experience reminded them that even with its

myriad challenges justice American-style is a cakewalk. Albanian judges often were

without telephones. Pens, pencils and paper were in short supply. "The judges there

were peacekeepers - wise people in the neighborhood" who persevered despite having

"no ability to enforce decrees or access laws," Utter recalls. Still, the American

volunteers felt as if they were making real headway. Then the nation's chief justice

was ousted. The judges' association disintegrated. The American Bar Association

volunteers stayed in touch with their frightened Albanian colleagues as best they

could. In a report for the American Judicature Society in 2001, Scott Carlson, CEELI's

director, said their work paid major dividends for democracy. Power had changed

hands in 1998 and a new Albanian constitution was ratified. Capitalizing on his

prestige and experience, Utter was quickly back on the scene "to give moral and

intellectual support to the new chief justice, with whom he had worked during the

judiciary's darkest days."

"We run him ragged," Carlson said of Utter's frequent trips. "Every hour is booked,

with lectures, meetings and lunches."

Utter has made six trips to China and several to Prague, where the Law Initiative

has an institute. He taught civil rights law to Kosovo attorneys, served as dean

of the faculty for the program for Iraqi judges and headed the delegation to the

Czech Republic with the People to People Comparative Law Study group. He headed

another American Bar Association trip to Cuba. At the same time, he has volunteered

with the U.S. State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development.

For his work with judges in emerging democracies, Utter received the CEELI Volunteers

Award from the American Bar Association in 2003. Of all the awards he has received

over the years, this one touches him the most. "But my work is a small pebble compared

with what others do," Utter says with characteristic modesty. "It's been a great

privilege. The greatest has been to see the dedication of people around the world

under incredible circumstances working to develop the rule of law in their own countries."

He points to a poll taken in Haiti in 2001 to gauge people's priorities. "In a country

with massive unemployment, brutality, corruption, poverty and a pervading sense

of hopelessness," Utter wrote, "the primary wish was for the availability of justice

for all and for a non-corrupt court system. … The fulfillment of this universal

longing for justice and access to a fair judicial system does not occur without

an investment of time, energy, commitment and courage."

Justice Utter, front row, center, poses

with faculty members and some of the Iraqi judges who attended an educational seminar

in Prague in 2004.

Justice Utter, front row, center, poses

with faculty members and some of the Iraqi judges who attended an educational seminar

in Prague in 2004.

Utter says the 140 Iraqi judges who attended CEELI's "Judging in a New Democratic

Society" seminars in Prague in 2004 and 2005 were among the brightest and bravest

he has ever met - judicial profiles in courage. One was assassinated on the way

to the conference; another told of seeing two of his bodyguards killed while protecting

him from an attack. One of the most committed institute participants was the Secretary

of the Iraq Council of Judges. He was assassinated when leaving home for work in

2005. One judge told of spending 17 years in Iranian prisons following his capture

during the war between Iran and Iraq. He had been conscripted into the army. Finally

freed and reinstated to the bench, he found his home destroyed by a stray artillery

shell and members of his family dead.

One judge asked Utter if he planned to give them grades. "Why would I do that?"

Utter said. The Iraqi judge smiled and in a classic bit of black humor quipped that

he'd been thinking of getting an "F" so he could stay in Prague. "And who could

blame him?" Utter says. "They would all be returning to conditions little known

to most other jurists of this world." As dean of the faculty and a senior instructor

at the CEELI Institute, Utter was inspired daily by his students. One day, after

a presentation on American, European and other judicial ethics codes, the instructors

"challenged the Iraqi judges to draft their own code. Asked what element they would

add that was not in the other codes, they replied, 'Courage,' noting that without

courage all other ethical principles were of no value." We Americans too often think

we wrote the book on democracy, Utter notes.

Utter with two Iraqi judges. Judge

Qais Hashem al-Shamari, right, was the Secretary of the Iraq Council of Judges.

He was assasinated in 2005.

Utter with two Iraqi judges. Judge

Qais Hashem al-Shamari, right, was the Secretary of the Iraq Council of Judges.

He was assasinated in 2005.

In the fall of 2008, Utter was part of a team that spent five weeks talking with

members of the United Nations' International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, where

in the space of three horrific months in 1994 three-quarters of a million people

were murdered - men, women and children hacked to death by machete-wielding soldiers;

fetuses ripped from wombs; unspeakable torture. One is tempted to suggest that some

Nazi death camps were humane by comparison. The Hutu extremists had set out to liquidate

the minority Tutsis and any moderate Hutus who dared protest. The members of the

war-crimes tribunal heard soul-searing testimony as they worked to bring ringleaders

to justice. Their work produced some landmark precedents in the annals of international

justice, notably establishing rape as genocide. During the reign of terror, women

were mutilated and murdered, destroyed "physically, mentally, emotionally." Sexual

violence was used to dehumanize, spread fear and disease.

The team that included Bob and Betty Utter, as well as former King County Superior

Court judge Donald Horowitz and former U.S. Attorney John McKay, now a law professor

at Seattle University, traveled to Tanzania and Rwanda to interview members of the

tribunal and survivors of the genocide. The oral histories and video interviews

became a compelling presentation called "Voices from the Rwanda Tribunal: Genocide

and Justice." The goal is to prevent another Rwanda by opening eyes and minds. If

the Nuremberg Trials of Nazi leaders had been followed by such a project, Utter

believes Cambodia's "killing fields," South Africa's poisonous apartheid regime

and the Rwandan atrocities might have been avoidable. At the very least, the world

would have been farther down the road to international justice.

The mediator

In 1997, after a mentally ill man fatally stabbed a retired Kent firefighter outside

the Kingdome in a random act of madness, King County Executive Ron Sims named Utter

to head a special task force to investigate how the mental health system deals with

misdemeanor offenders. The attacker earlier had been sent to Western State Hospital

for psychiatric examination after stealing a bicycle. It wasn't the first time he'd

been in trouble, and he assaulted two state employees during his confinement. Nevertheless,

he was sent back to the County Jail and eventually released with no further treatment.

"I can't think of anyone better than Justice Utter" to head the task force, said

Sims. "He brings his integrity, his sense of justice and his sense of humanity to

this important task" and "is ideally suited to finding out how we fix the system."

The result, in 1999, was the formation of a now nationally recognized therapeutic

court that strives to promote cooperation between mental health treatment providers

and the criminal justice system, two systems that usually have not been close allies.

The Mental Health Court, one of the first in America, celebrated its 10th anniversary

in February of 2009. "The work of this court for the past decade is a testament

to how collaborations like this can reduce incarceration costs while also improving

lives and protecting public safety," said Judge Barbara Linde, presiding judge of

the King County District Court.

In 1998, Utter became the fledgling Washington News Council's first chairman and

stayed with it for six years. The independent, nonprofit group strives to promote

accurate and balanced news media coverage. Utter "did a superb job, as you might

expect, presiding over our hearings with absolute even-handedness," says the council's

executive director, John Hamer.

"Hamer's invitation to Bob to preside over the first hearings of the News Council

was a stroke of genius," says Cliff Rowe, a communications professor at Pacific

Lutheran University who served on the council for several years. "I had long admired

Justice Utter as an articulate voice for press freedom, and his willingness to accept

the chairmanship immediately put a recognizable face of fairness and dignity on