"Woman

Wields the Gavel," the Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s Society section declared

in 1968. Reporter Kay Kelly noted that most people would expect a judge to be a

solemn, white-haired, 60ish man. But Carolyn Dimmick – "blonde, attractive, young,

pleasant, fun, fashion-conscious and the proud mother of two" – was "a surprise

and a treat." According to colleagues, she was "also a very competent judge," one

of only three women on the bench statewide. However, she was "reluctant to talk

about herself, reluctant to consent to publicity. But why should Kirkland keep her

to itself?"

Why indeed? Carolyn Dimmick graduated quickly from being a surprise, but 40 years

later she’s still a treat, and still wielding a gavel now and then as a senior judge

on the U.S. District Court bench in Seattle. She’s youthful and fun, yet dignified

as befits the occasion. The proud grandmother of four, she’s reluctant to talk about

herself, and not just "a very competent" judge but one of the most respected and

influential judges in Northwest history.

A role model for her own generation and all since, Judge Dimmick had to run a gauntlet

of those "she’s-a-woman-and-a-judge – imagine that!" – stereotypes before she became

Washington’s first female Supreme Court justice in 1981. Even then, her old boss,

former King County prosecutor Charles O. Carroll, introduced her after her swearing

in as "the prettiest justice on the Supreme Court."

Justice Jim Dolliver, who received his law degree from the University of Washington

a year before Dimmick, knew she was a lot more than just a pretty face. In a classically

puckish Dolliver touch, he passed her a note on their first day together on the

bench: "Which do you prefer: 1) Mrs. Justice. 2) Ms. Justice. 3) O! Most Worshipful

One, or 4) El Maxima?"

"All of the above!" Dimmick wrote back, laconic as ever.

Nineteen-eighty-one was a landmark year for women and the judiciary. A few months

after Dimmick donned the robe in Olympia, President Reagan nominated Sandra Day

O’Connor of Arizona to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Dimmick’s office at the Federal

Courthouse in Seattle, there’s a framed photo of her with Justice O’Connor. Born

just a few months apart, they have a lot in common, notably nimble minds and a reluctance

to be labeled. Judge Dimmick was gratified when O’Connor was named to the high court,

but thinks the idea of appointing a woman simply because she is a woman is "demeaning."

Back row, from left: the Washington

Supreme Court in 1982: Fred Dore, Floyd Hicks, William Williams, Carolyn Dimmick.

Front row, from left: Robert Utter, Hugh Rosellini, Bob Brachtenbach, Charles Stafford,

James Dolliver

Back row, from left: the Washington

Supreme Court in 1982: Fred Dore, Floyd Hicks, William Williams, Carolyn Dimmick.

Front row, from left: Robert Utter, Hugh Rosellini, Bob Brachtenbach, Charles Stafford,

James Dolliver

Dimmick’s 40-year tenure as a judge on county, state and federal courts "covers

the span of time when women judges went from novelty to majority," says Robert S.

Lasnik, her colleague on the U.S. District Court in Seattle. Lasnik, who succeeded

Dimmick when she went on senior status in 1997, describes her as "a unique blend

of wisdom, humility, humor and charm."

Dimmick’s coming-out party as a lawyer occurred on Sept. 21, 1953, when the Post-Intelligencer

devoted a three-column photo and a breezy story to "Pretty Blonde Water Skier Qualifies

as Attorney":

"Carolyn Joyce Reaber, 23, blonde and beautiful Seattle water skier, will be sworn

in as an attorney-at-law this Monday. ... Last Friday, the day she waited for the

bar examiners to announce whether she had passed or not, was the worst day in her

life, Miss Reaber said, a lot worse than the day she went up Hell’s Canyon Rapids

on water skiis with a movie camera trained on her." Besides being a semi-pro water

skier with the Ski-Quatic Follies on Lake Washington, the story said she had been

a part-time employee in the P-I’s Circulation Department from the time she was a

sophomore at Lincoln High School until her senior year at the University of Washington.

So the press took a shine to her as one of its own, but she was a bona fide trailblazer.

Fate, however, is a recurring theme in her life story. Seattle Times reporter Dick

Clever once observed: "If the law curriculum at the University of Washington in

the early 1950s had included a math prerequisite, the state still could be waiting

for its first woman Supreme Court justice." In fact, Carolyn Reaber hadn’t even

considered becoming an attorney when she enrolled at the university in the fall

of 1947. She concentrated on business and sociology. However, after three years

she had to declare a major to earn a degree. "I went through the catalogue and found

that you didn’t need a math prerequisite for a law major," the judge recalls. Moreover,

after three years of study, UW undergrads in that era could apply for admission

to the Law School and receive a B.A. after completing their first year there. "Enthused

by a business law class earlier in her studies, she thought a year in law school

would be a less painful way to a college degree," Supreme Court historian Charles

H. Sheldon notes. "She thrived on the law curriculum," and her classmates elected

her to a prestigious spot on the Law Review. She had to forgo that opportunity because

she was still working part-time at the Post-Intelligencer.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day

O’Connor, left, with Carolyn Dimmick, center, Robert Lasnik, right, and Chief Magistrate

Judge Karen Strombom in back

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day

O’Connor, left, with Carolyn Dimmick, center, Robert Lasnik, right, and Chief Magistrate

Judge Karen Strombom in back

Dimmick graduated in 1953, one of only three women in her Law School class. Four

others had dropped out along the way. She immediately landed a job as an assistant

attorney general in Olympia. "I never dreamed of applying at a (Seattle) law firm.

Public service was the only show in town" for women attorneys at that time, Dimmick

recalls.

In 1955, she joined the King County Prosecutor’s office, where she was detailed

to woman’s work in the Domestic Relations Division. Her file of press clippings

punctuated with incredulity grew bigger as the P-I duly noted, "Carolyn J. Reaber,

a blonde young woman whose appearance hardly squares with the public conception

of what women lawyers look like, became divorce proctor of King County Wednesday.

... Miss Reaber, five feet 2½ inches tall, is nevertheless armed with all the legal

license necessary to tangle in the courtroom with any giant of the profession. ...

Her duties as a divorce proctor will consist principally of protecting the interests

of children and ascertaining that grounds for divorce exist."

By 1956, she was a young married woman and moving up to tangle with perverts and

busybodies. "Blonde Barrister Assigned to Morals Detail" was the headline:

"Each Thursday is morals day in King County Justice Court," the P-I reported. "As

a rule, the prosecution is represented by a petite blonde who, frankly, doesn’t

look the part. ...Carolyn Reaber Dimmick is young, pretty and soft spoken. More

like a ‘big sister’ with her blonde hair swept into a youthful pony tail, she is

able to put her young plaintiffs at ease as they relate frequently sordid details

to Judge J. William Hoar."

Dimmick shared the story of the "elderly spinsters who reported a neighbor for indecent

exposure. Investigators reported the two homes were some distance apart. Quizzed

on how they knew of the neighbor’s misconduct, they answered, ‘We used our field

glasses!’ "

Carolyn met her future husband, Cyrus A. Dimmick, in 1953 when they both worked

for the Attorney General’s Office. Cy was 11 years older, "a big, tall, good-looking

guy," Carolyn recalls, and a decorated veteran of World War II who had graduated

from the UW Law School in 1948. They were married in 1955. Cy established a private

practice in Seattle. The couple had two young children by the early 1960s, and Carolyn

took breaks from her county job, doing legal work from home or in Cy’s law office.

"Without that opportunity," she recalls, "I would have just lost my profession for

all those years. Instead, I was able to keep up."

It was at her husband’s urging that she applied for the Northlake Justice Court

seat in 1965. The county commissioners were impressed by her demeanor and enthusiasm

and she had Chuck Carroll’s endorsement. Carolyn told Cy, "You don’t have to call

me ‘your honor.’ Just call me ‘judgie.’ That’ll be good enough."

Despite her pluck and intelligence, Dimmick "was terribly discouraged early on and

felt like giving up" as she encountered the inertia of a male-dominated legal profession.

Women were torn between motherhood and careers, especially when there were so many

gender-based roadblocks in the workaday world. No bra-burner, Dimmick nevertheless

celebrated the power of sisterhood in the Women’s Liberation era. "In the 1970s,

Washington women lawyers were getting organized," she recalled 27 years later. "Grouping

together gave us courage. And we overcame."

In 1976, Dimmick was appointed to the King County Superior Court bench by Gov. Dan

Evans. Her friend and future Supreme Court justice Charles Z. Smith devoted his

commentary on KOMO TV to the occasion, concluding that "The fact that she’s a woman

is important ... but it really has nothing whatever to do with her competence as

a judge. ... Ability and integrity in the law is measured by performance and not

by whether one’s a man or a woman."

In the fall of 1978, Dimmick’s sense of integrity in the law had her on the hot

seat after she ordered striking Seattle teachers back to work. Peeved, the King

County Labor Council withdrew its endorsement of her even though her term as Superior

Court judge didn’t expire for two more years. James Bender, the executive secretary

of the Labor Council, said the unions were upset because Dimmick not only signed

a preliminary injunction ordering the teachers back to work, she declared that all

public-employee strikes were illegal. "That broad stroke was out of order," Bender

asserted. "She was trying to legislate." Unfazed, Dimmick said she was doing no

such thing. "If they are going to fault judges for upholding the law," the judge

said, "that’s the way the ball bounces. It is common law that governmental employees

cannot strike. Either the Supreme Court or the Legislature would have to change

that."

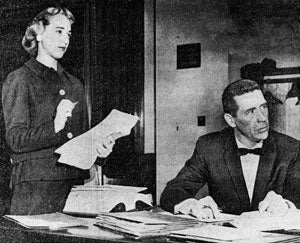

Graduation from the University of Washington

School of Law in 1953

Graduation from the University of Washington

School of Law in 1953

The president of the Seattle-King County Bar Association, William A. Helsell, chastised

the Labor Council in his column in the Bar Bulletin, noting that attorneys who had

appeared in Dimmick’s court all said she "calls them as she sees them." He added,

"The King County Labor Council should be grateful that we have Superior Court judges

of ability and integrity who will not be swayed by one pressure group or another,

but who patiently and carefully decide cases on the basis of the law and the facts."

Ed Donohoe, legendary editor of the Washington Teamster newspaper – once described

as "the Don Rickles of the typewriter" – wrote about the dust-up in his widely read

"Tilting the Windmill" column: "In defense of Judge Dimmick, she was among a dozen

King County jurists who refused to attend a convention at Ocean Shores because the

resort was on the unfair list, and she is considered one of the most intelligent

and fairest persons on the local bench – attributes that seen to be in short supply

these days."

Labor came around, Dimmick was re-elected without opposition and 1980 found her

poised to move up once again. In the last days of her administration, Gov. Dixy

Lee Ray "was definitely looking to appoint a woman to the state’s highest court,"

Judge Dimmick says. "I was in the right place at the right time." In fact, she was

more interested in another place at that time – the Court of Appeals. That’s the

job she applied for when Fred Dore won election to the State Supreme Court and vacated

his seat on Division One. When Dimmick met with Gov. Ray, she assumed she was being

vetted for the Court of Appeals. Dixy had something else in mind. There was also

a vacancy on the Supreme Court in the wake of the death of Justice Charles T. Wright,

and the governor announced Dimmick’s appointment with "great pride."

Surprised to learn she was about to make history, Dimmick seized the opportunity,

but "had the only vacancy been the Supreme Court, I would not have applied," she

recalls. Mainly, she was less than enthused about moving to Olympia.

Carolyn and her husband Cyrus "Cy"

Dimmick in the early 1960s

Carolyn and her husband Cyrus "Cy"

Dimmick in the early 1960s

On Jan. 2, 1981, Cy Dimmick helped his wife don her new robe. "I told him not to

kiss me because no one is going to kiss the other justices," she quipped. She also

told the crowd that her first job after law school was as a clerk in the Attorney

General’s Office, then located in the Temple of Justice. "I never had the slightest

dream I would be able to sit here myself," she said.

When Carolyn Dimmick broke into the old boys’ club at the Supreme Court, there was

only one bathroom for the nine justices. Justice Floyd V. Hicks told her it would

cost $50,000 to $60,000 to install a second bathroom to accommodate her. "Not on

my watch!" Dimmick declared.

The judge is imbued with common sense and the common touch. There is no artifice.

The press described her as a "judicial conservative" when U.S. Senators Dan Evans

and Slade Gorton recommended her to President Reagan in 1984 for a seat on the federal

bench. However, it went unmentioned that while she was tough on hardened criminals

and brazen scofflaws, she was also inclined to be lenient with first offenders and

those involved in non-violent crimes. Even some rapists, "especially repeaters,

need special kinds of help," she said in 1976 when she was a Superior Court judge.

"We know why burglars burgle – they think it’s a way to make a living. But rape

– that’s still a question ... I think many women are too willing to lock them up

and throw away the key. I believe in tough dealing, but also in practical help."

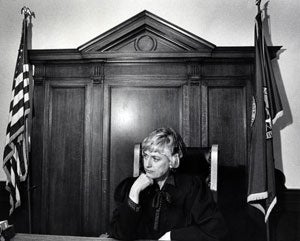

Dimmick on the King County Superior

Court bench during arguments over the Seattle teachers’ strike in 1978.

Dimmick on the King County Superior

Court bench during arguments over the Seattle teachers’ strike in 1978.

In a 1984 interview, Dimmick said labels "are stupid" because every good judge decides

a case on the issues. Still, "During her four years on the state’s high bench, Justice

Dimmick became perhaps the most conservative member regarding criminal matters,"

according to Sheldon. By the end of her tenure at the Temple of Justice, she was

"disagreeing most often with moderate-to-liberal Justices Robert Utter (an arch-foe

of the death penalty), James Dolliver and Vernon Pearson. She often found herself

in the minority, filing dissents."

But she genuinely liked and respected those fellows, and when she disagreed, she

strived not to be disagreeable. "When I write a dissent, I hope to get (enough votes

to win the) case," Dimmick told the Supreme Court historian. "Sometimes I’ll write

a dissent because I’m outraged ... I want to open their eyes. ‘What are you doing

here?’ I’ll use rather stark language. I want to get their attention but I don’t

want to be overbearing. ..."

Dimmick agonized over the Washington Supreme Court’s 1981 ruling (State v. Frampton,

95 Wn2D469) declaring the state’s death penalty statute unconstitutional. Dimmick

was among the dissenters in the complex, 5-4 decision. "I can’t imagine anything

more traumatic for any of us," she remarked later in the year. "Everybody had their

strong, sincere convictions of what the law was – not what they felt personally

but what the law required. And that’s what makes it difficult." She emphasized that

it is a legislative function to make sure the law is correct.

Both Houses of the Legislature quickly passed a new death penalty bill and sent

it to Gov. John Spellman, who signed it into law.

Carolyn Dimmick poses with her family

after being sworn in to the Washington Supreme Court on January 2, 1981. From left:

Her daughter Dana, husband Cyrus, Carolyn, her parents, Margaret and Maurice Reaber,

and son Taylor.

Carolyn Dimmick poses with her family

after being sworn in to the Washington Supreme Court on January 2, 1981. From left:

Her daughter Dana, husband Cyrus, Carolyn, her parents, Margaret and Maurice Reaber,

and son Taylor.

Charles Rodman Campbell, whose name will live in infamy, was the poster child for

Judge Dimmick’s belief that the death penalty is merited for some savage crimes.

She has now concluded, however, that "it’s outdated because it’s too expensive"

– witness the fact that Campbell wasn’t executed until 10 years after she wrote

the majority opinion in a 5-4 Supreme Court decision in 1984 that affirmed his death

sentence for three incredibly vicious murders.

The debate still rages over whether the death penalty is unconstitutional, but no

one argues that Campbell’s crimes were not "cruel and unusual." He was on work-release

from prison in 1982 when he murdered a woman he had raped and sodomized eight years

earlier while holding a knife to her infant daughter’s throat. Returning for revenge,

he also killed the child – by then 8 – and a neighbor woman who had testified against

him. He slashed their throats. Executioners had to strap the struggling Campbell

to a board before they could fasten the noose around his neck. They later discovered

that he had been sharpening a four-inch chunk of metal to create a blade.

"He was one," Judge Dimmick says with disgust. "Ugh!"

Above all, a judge’s job is to interpret and uphold the law, Dimmick says, not make

the law. On the federal bench in 1995, she overturned the murder conviction and

death sentence of a man who killed a Clallam County couple who had befriended him

while he was in prison for armed robbery. Two jurors testified that during the trial

they heard another juror mention that the defendant had a prior criminal record.

Dimmick’s view was that the comment caused "no prejudicial error," but she pointed

out that the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals made it clear her job was to determine

whether juror misconduct had occurred. If it had, she was obliged to throw out the

conviction.

In another notable case, Judge Dimmick in 1996 upheld the state’s sex-offender public

notification law, denying a constitutional challenge by three recently released

sex offenders who had argued that the law subjected them to further punishment in

the form of harassment and ridicule. Dimmick concluded that "...The stigma of which

plaintiffs complain is not created by the registration and notification provisions

of the sexual-offender registration law but rather by the community’s reaction to

(the sex offender’s) prior conduct."

"She didn’t just teach me about the law," says Dan Johnson, a Seattle attorney who

was her law clerk in 1997-98. "She taught me about patience, tolerance and rising

above personal disputes to seek justice."

One of Dimmick’s favorite quotes is from the famed legal scholar Roscoe Pound: "The

law must be stable, but it must not stand still." Just when some people think they

have her pigeon-holed, she demonstrates her intellectual independence. In a 1988

opinion from the federal bench overturning a Bellingham ordinance targeting pornography

as dehumanizing to women, Judge Dimmick wrote, "...much as alteration (of sociological

patterns) may be necessary and desirable, free speech, rather than the enemy, is

a long-tested and worthy ally. To deny free speech in order to engineer social change

... erodes the freedoms of all and threatens tyranny and injustice ..."

In 1993, another free speech case offered some levity, but Dimmick again showed

her stripes as a First Amendment protector when she balked at banning an environmental

group’s ads depicting Smokey Bear as a chainsaw-wielding tool of the U.S. Forest

Service.

The late Richard F. Broz, a former King County Superior Court judge and assistant

U.S. attorney, called Dimmick the "quintessential judge" – "firm, fair, courteous"

and hard-working, but also possessed of "a light touch."

On the federal bench, Judge Dimmick enjoyed the short-lived 1997 case of a self-described

"milk-a-holic" who blamed his health problems on a life-long weakness for milk.

Naming Safeway and the Dairy Farmers of Washington as defendants, he claimed "milk

is just as dangerous as tobacco" and asked Dimmick to order warning labels on milk

containers and regulate all dairy-product advertising. "Dismissed," said the judge,

clearly unmooved.

Two good friends, Supreme Court Justice

Carolyn Dimmick and King County Superior Court Judge Barbara Durham at a banquet

in 1992.

Two good friends, Supreme Court Justice

Carolyn Dimmick and King County Superior Court Judge Barbara Durham at a banquet

in 1992.

In 1995, while serving as chief judge of the U.S. District Court, she dismissed

a class-action lawsuit by a Seattle attorney attempting to recover damages for businesses

impacted by the 1994 Major League Baseball strike. Noting that on at least three

occasions the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that similar issues were beyond the scope

of federal antitrust laws, Judge Dimmick said the case at hand "presents a situation

that the baseball sage Yogi Berra might describe as ‘déjà vu all over again.’ "

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals once referred to Judge Dimmick’s analysis

of a particularly tricky case as "Solomon-like." Trial lawyers say she has the "perfect"

judicial temperament. "You can’t put anything over on her," a veteran attorney noted.

Speaking of Solomon, in 1984 Dimmick wrote eloquently for a unanimous State Supreme

Court in a "wrongful birth" case that made headlines. A woman and her spouse sued

a doctor who performed a sterilization. Despite the tubal ligation, the woman became

pregnant and delivered "a healthy, normal child." The couple sought damages to compensate

for the costs and "emotional burdens" of rearing and educating the unplanned child.

Justice Dimmick concluded that they were entitled only to medical and other expenses

directly related to the child’s birth. "A child is more than an economic liability,"

she wrote. "A child may provide its parents with love, companionship, a sense of

achievement and a limited form of immortality. ... The child may turn out to be

loving, obedient and attentive or hostile, unruly and callous. The child may grow

up to be president of the United States or to be an infamous criminal."

In the final analysis, Dimmick said, it’s impossible to weigh with reasonable certainty

the costs of raising a child against the emotional benefits of parenthood. "It is

a question which meddles with the concept of life and the stability of the family

unit. Litigation cannot answer every question; every question cannot be answered

in terms of dollars and cents." Further, the judge said she and her colleagues were

convinced that there could be significant harm to the child as it grew older and

discovered it was unwanted – "an ‘emotional bastard,’ who will someday learn that

its parents did not want it and, in fact, went to court to force someone else to

pay for its raising. ... It will undermine society’s need for a strong and healthy

family relationship. We have not become so sophisticated a society to dismiss that

emotional trauma as nonsense."

It was Dimmick at her most sagacious, mulling facts, sorting through precedents,

testing the letter of the law with common sense.

Judge Lasnik says, "She never was a doctrinaire conservative. ... On the state Supreme

Court, she was able to forge alliances with people from both the liberal wing, like

Justice Dolliver, and people who were even more conservative. It’s way too much

of a stereotype to say she’s ‘to the right of’ because on Social Security cases

or cases involving people who were hurting and needed relief, she can be a real

softy too. She’s not the kind of judge you come away talking about her intellectual

capacity. It’s there but it doesn’t jump out at you as much as the graciousness,

the courtesy, the respect, the relaxed manner, which are much more important in

a lot of ways. I’m not saying she didn’t have tremendous intellectual power, but

she is so modest and so self-effacing that she comes across much more as the people’s

judge."

Lasnik adds, "I think the thing that’s underestimated about her, especially concerning

her years on the state Supreme Court, is that she can (bring people together). As

the first woman on the state Supreme Court, you know that is a tough place to suddenly

change. Sandra Day O’Connor did it a year later with the U.S. Supreme Court. The

kind of person who is first is always so important .... Just as Justice Sandra Day

O’Connor turned out to be a remarkable pick for Ronald Reagan, Carolyn Dimmick turned

out to be the perfect person because she was able to make her male colleagues adjust

and accept without ever making them feel put upon, or under attack."

Reagan was certainly impressed. "We’ve read all your decisions," the president told

Dimmick when he called to say she was his pick for the federal bench.

During her 20 years on the bench before the federal court appointment in 1985, Dimmick

had been scrupulously nonpartisan, even though a biographical history of the State

Supreme Court lists her as a Republican. That derives from the fact that like every

other deputy during Chuck Carroll’s powerful career as King County prosecutor and

county GOP chairman, Dimmick was required to make speeches for the Republican cause

and boost the boss’s career.

The federal bench was a plum job that Dimmick happily accepted. Living during the

week in Olympia and returning home to Seattle on weekends wasn’t the best situation,

and federal judges serve for life under the provisions of the U.S. Constitution.

Moreover, she would be presiding over a trial court rather than an appellate court,

and Dimmick found that arena much more stimulating. She was also dismayed by the

tedium of raising a campaign war chest and running for re-election, even though

she shellacked her opponent in 1984. She is appalled by what judicial campaigns

cost these days.

Dimmick took a considerable risk to ensure that her dear friend and kindred judicial

soul, Barbara Durham, would succeed her on the State Supreme Court. On Jan. 14,

1985, immediately after she was sworn in for a new term of office and assured that

her nomination to the federal bench was in the works, Dimmick resigned so that Governor

John Spellman, a Republican, could appoint Durham on his last day in office. Governor-elect

Booth Gardner, a Democrat, likely would have been otherwise inclined. By April,

Dimmick had been confirmed to the federal bench by the U.S. Senate.

Durham went on to become the first-ever female chief justice. She called Dimmick

a powerful role model. They met in the 1970s when "she was a district court judge

in Redmond, and I was a brand-new judge on the Mercer Island District Court," Durham

recalled in 1994. "I called her because she was the only other woman judge I knew.

We had lunch together, and she told me what to do and what to expect."

Tragically, Justice Durham died at the age of 59 in 2002 of kidney failure, a complication

of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Judge Dimmick was devastated by the loss of

her friend. "She was a saint to Barbara Durham when she started to decline," says

Judge Lasnik.

Judge Betty Howard, seated center on

ottoman, at a Christmas party at the Dimmick home in the 1980s with some of the

female lawyers she had befriended and mentored over the years. Carolyn Dimmick is

in the back row, fourth from left.

Judge Betty Howard, seated center on

ottoman, at a Christmas party at the Dimmick home in the 1980s with some of the

female lawyers she had befriended and mentored over the years. Carolyn Dimmick is

in the back row, fourth from left.

Carolyn Dimmick is loyal, and a friend for all seasons. Among her own mentors was

Betty Taylor Howard, a big, brassy district court judge Dimmick met when she was

still undecided about finishing law school. Howard had her spend some time in her

courtroom. Referring to the lawyers who’d appeared before her that day, the judge

said, "Well, you could do that."

Said Dimmick, "Well, I could certainly do it better than they’re doing it."

Howard said, "You might as well keep going to law school. What are you going to

do?"

Dimmick said, "Well, keep working at the P-I."

"And Betty said, ‘Nah, keep going to law school.’

"So I did. And she was then my mentor forever."

They spent every Christmas Eve together for 50 years – the rest of Judge Howard’s

life.

Former justice Faith Ireland – one of a five-member female majority on the State

Supreme Court from 2003-2005 – says Dimmick was a mentor to all of the women who

appeared in front of her or worked with her. "She always remains the same pleasant,

plain-speaking, no nonsense person, no matter what position she has achieved. ...

She has personal warmth but is firmly in control in the courtroom. ... When I would

lose a case, she would call me back into chambers and gently explain why I lost

and encourage me to keep trying cases."

"She was a wonderful trial judge," Dimmick’s longtime law clerk, Cheryl Bleakney,

said in 2003 when the judge received the William L. Dwyer Outstanding Jurist Award.

"She was unfailingly gracious and respectful to attorneys, witnesses and especially

jurors. And that gracious, warm exterior covers a first-rate legal mind."

Among those who know Dimmick best is Georgia Kravik, her judicial assistant/law

clerk. Kravik started out babysitting the judge’s children, then became her Superior

Court bailiff. They’ve been friends for 44 years. "Above all, she is a person without

affectation who treats everyone who comes before her with respect," Kravik says.

"The private Carolyn Dimmick is the same. What you see is what you get. Her overriding

charm, though not without healthy boundaries, is that she likes people. Carolyn

is a friend-keeper, with a variety of people in her life, including grade school

friends of 65 years, high school friends she still sees regularly and law school

buddies. For me, it is great fun to be one of the many people who have been invited

into the orbit that surrounds this stimulating woman’s life."

Debra Stephens, the newest female member of the State Supreme Court, called Judge

Dimmick after she was appointed by Gov. Chris Gregoire in 2007. "I was a little

nervous about doing it because I had never met her, except at a reception," Stephens

says, "but I was aware when I was appointed that the seat I hold was Judge Dimmick’s

seat, and this seat has been held by a woman ever since. I admire all of the women

who have served before me. But she was the first and I just wanted to share with

her how much her career has done to inspire later generations of women lawyers and

judges. So I just took a chance and called her up and said, ‘Gosh, if you have time

I’d love to have coffee,’ and she was incredibly gracious. Not only did she immediately

say ‘Yes,’ she invited me up to her chambers and gave me a great tour of the new

Courthouse. ... Until then, I was unaware that she had such a role in the design

of the building, everything from the layout and functionality to the art. She and

I discovered we share a love of architecture and design. ... We just became fast

friends."

Judge Dimmick has an artist’s eye and a strong sense of thrift. After going on senior

status in 1997, she devoted much of the next seven years to overseeing planning

and construction of the new $171 million U.S. Courthouse in downtown Seattle. Her

fellow judges told the 9th Circuit they wanted her to be their go-between with the

General Services Administration, the architects and contractors. She called herself

"the tenant representative."

Critics said the northern tip of the retail district at 7th and Stewart was a poor

site, especially given the need for heightened security in the wake of the devastating

bombing of the Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995. "I have a hard time seeing

how a courthouse that is fortress-like will contribute to the retail core," said

Seattle City Councilman Peter Steinbrueck. Judge Dimmick countered that the courthouse

would spur new development, including new legal offices. Noting that the building

would include grass, trees, artwork and a plaza open to the public, she vowed that

it wouldn’t be "a clunky concrete box."

On site practically every day, Judge Dimmick immersed herself in the details of

the 23-floor, 615,000-square-foot project. "She was our eyes and ears," says Judge

Lasnik, "and she did a fabulous job." Another of her colleagues, Judge John Coughenour,

said, "Everyone – from the construction workers to the architects – loves working

with her, and people listen when she talks."

"There was no other person who could have pulled it off as well as Carolyn Dimmick

did," Lasnik says, "because she had the clout with her colleagues to force us to

sit down and deal with issues now when we’re planning the building, rather than

complain about them later. But she also helped the architect and the design people

because they can’t get a judge to make a decision, but she can. She could come and

say, ‘OK, here’s three possible fabrics you can have. Make a choice.’ She dragged

us down to a warehouse in south Seattle where there was a mock courtroom set up.

And she said, ‘Sit in the chair. Look at the sight-lines. This is what you’re going

to get. Complain about it now when I can do something about it. Wait until it’s

built, and I can’t do anything about it.’ She had the ability to speak with architects

and designers because she has such personal design sensibility. And the trades people

– the construction people – adored her because she’d put on a hardhat and go out

with them. She was just like somebody’s mom or aunt. And they thought ‘Man, this

is great.’ They wanted to do it right for the judge because she’s so neat. She’s

so cool. There’s not another judge in the building who could have been able to deal

with all those groups, and successfully."

When budget constraints required compromises, Dimmick was in thick of things. "We

had to re-think and re-plan to come in on budget," she recalls, "but we didn’t change

the quality or efficiency of the building." She helped ensure that modest materials

produced an interior that is simultaneously striking and utilitarian, with state-of-the-art

courtrooms. Every two years, the General Services Administration honors "The Best

of the Best" federal projects in the nation. When it opened in 2004, Seattle’s new

federal Courthouse received the highest honor from a panel of private-sector architects

and builders, who noted that it was "completed on time and on budget, despite significant,

unexpected challenges that included record inclement weather, a labor strike, the

departure of a major joint venture partner and contaminated soils."

Judge Dimmick’s husband of 51 years died in 2006. A solid lawyer, his "real career

was golf," she quipped. In fact, Cy Dimmick’s obituary observed that "to say he

was a serious player is like saying Dickens was a serious writer." Cy doubtless

would have loved that line, which was penned by his son-in-law, Bradley Scarp, much

to the delight of the whole family.

When she was a King County District Court judge in 1969, Dimmick told a feature

writer that she liked to go "junk-tiquing," enjoyed water sports and was "planning

to take up golf, which her husband plays enthusiastically." We asked if she had

ever taken up golf. The look on her face said, "Surely you jest?"

"I did take a couple of lessons at Cy’s request ... from Charlie Mortimer, the pro

over at Inglewood Golf Club. Charlie would say, ‘You haven’t been practicing.’ And

I’d say, ‘No Charlie, I’m working. I don’t have time to practice.’ He said, ‘You

know, I don’t have time to teach you.’ I said, ‘It’s a deal!’ And that was the end

of it. ... I planned to take it up, but it didn’t take. Let’s put it that way. If

you could do it without having to practice I could have done it."

When it came to the law, practice was more joy than work for Carolyn Dimmick. The

woman who had all those mixed emotions about being a lawyer has mastered every law

job she’s had since 1953.

From her art-filled, immaculate 16th floor office overlooking the Space Needle and

Puget Sound, the view is spectacular and the job still satisfying. A remarkably

youthful 79, she’s not ready to fully retire. But how would she like to be remembered?

"Old. A hundred years old. How about that? ...I never met a legal job I didn’t love.

Each one had its own aura and interest. It’s been a wonderful career."

Kirkland couldn’t keep her to itself.