Dunbar, the Engineer

As her academic career neared its end, Dunbar had earned both a Bachelor of Science

Degree in Ceramic Engineering and a Master of Science Degree in Ceramic Engineering

from the University of Washington in 1971 and 1975 respectively. (Later, in 1983,

Dunbar earned a doctorate at the University of Houston in Mechanical/Biomedical

Engineering.)

In 1973, she accepted her first corporate job. As systems analyst for The Boeing

Company, Dunbar got a taste of the working world and the occasional cynics who doubted

she could succeed. But Dunbar never paid much attention.

"I never saw them. I know that sounds really hard to believe. But they may have

been out there. Many years later, I heard about what people said. Either I selectively

decided not to hear, or I always looked at it as a challenge."

And she never gave the gender barrier much thought.

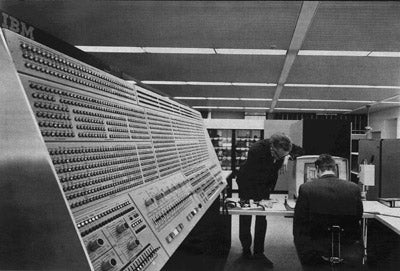

Computers have come a long way since

Dunbar began her engineering career in the male-dominated world of 1973. Her first

stint as a computer programmer is on an IBM 360 big enough to fill a room.

Computers have come a long way since

Dunbar began her engineering career in the male-dominated world of 1973. Her first

stint as a computer programmer is on an IBM 360 big enough to fill a room.

"If you go in with a chip on your shoulder, you're never going to make friends with

your colleagues. I just set out do my job."

At Boeing, Dunbar enjoyed testing her logic as a systems analyst and a problem solver.

"Computers don't have their own minds. We program them. If the computer followed

the wrong instructions it's because a human being wrote the wrong instructions,"

she says practically.

At the encouragement of another adviser, Dunbar packed her bags for Oxford, England,

nearly 5,000 miles (8,047 km) away. She wanted to pursue the opportunity and the

income of a visiting scientist position helped. Dunbar was destined for Harwell

Laboratories to work on advanced material for high-energy density batteries. "There

were only a few places overseas that were actually doing work in my research field,"

says Dunbar. “One of them was in Toulouse, France, and the other was at Harwell

Labs."

Dunbar later landed at Rockwell International's Space Division in Downey, California

where she worked on the production of ceramic tiles for the Space Shuttle. She made

her second attempt at the U.S. Astronaut Corps and this time became a finalist.

Eventually, Dunbar was made Payload Officer in Mission Control at the Lyndon B.

Johnson Space Center and Guidance and Navigation Officer for Skylab. She was closer

than ever to realizing her dreams.

The Pathfinders

The defining moment finally materialized two years later, in the spring of 1980,

when Dunbar officially became an astronaut candidate. At the time, no American woman

had flown in space. But a long line of daring female aviators set the stage.

In 1932, the legendary Amelia Earhart became the first woman to pilot an aircraft

across the Atlantic Ocean alone. The quantum leap was even more noteworthy for a

woman who, at age ten, remarked upon seeing her first airplane, "It was a thing

of rusty wire and wood, and looked not at all interesting." Curiosity got the best

of Earhart, however, when she witnessed a stunt flying exhibition nearly a decade

later.

"We thought we'd died and gone to heaven!" exclaimed female war veteran Caro Bayley-Boscoa

of the flying experience. When World War II erupted, "WASPS" - Women Air Force Service

Pilots - climbed behind the controls of American military aircraft and broke the

gender barrier along the way. They were the first females to pilot the war machines.

"I could be a nurse, a librarian, or a teacher," remarked fellow "WASP" Kaddy Steele.

"Those were my choices, if it wasn't for the war and the fact that they were so

short of pilots that they condescended to let us enter the sanctom sanctorum. And

they let us know that. They let us in because they needed us. They needed pilots."

The glass ceiling chipped yet again on May 18, 1953 when Jacqueline "Jackie" Cochran

surpassed the speed of sound six years after her male counterpart, Chuck Yeager.

For her part, Dunbar is one of just 48 women in history to enter the U.S. Astronaut

Corps and the only female astronaut from Washington. Worldwide, she joins the ranks

of just 51 women ever to fly in space. (Editor's Note: NASA statistics included in

this biographic profile are current as of June, 2009.) Despite the achievements

of female aviators and explorers throughout history, women at NASA remain greatly

outnumbered by men. In 1981, when Dunbar was first selected as an astronaut, women

made up only 22% of NASA's permanent workforce. By 2009, the female population at

the space agency grew to 36%.

Nicknamed the Vomit Comet, the KC-135

gives Dunbar and crew a sense of weightlessness over the Gulf of Mexico.

NASA photo.

Nicknamed the Vomit Comet, the KC-135

gives Dunbar and crew a sense of weightlessness over the Gulf of Mexico.

NASA photo.

The Vomit Comet

Bonnie Dunbar got her first real taste of the astronaut's world on a stomach-turning

flight over the Gulf of Mexico. The KC-135 dubbed "Weightless Wonder" or "Vomit

Comet" could reduce the force of gravity with steep climbs and dives along the Equator.

"It's kind of like scuba diving," says the five-time space veteran, grappling with

the difficulty of explaining microgravity. "But freer. You have less equipment and

you breathe air." The trick, she says, is not to exert too much force in your movements.

(Editor's Note: Zero gravity does not refer to an absence of gravity altogether, only

lower gravity than the Earth norm or a microgravity environment.)

For 18 months, Dunbar immersed herself in the astronaut's world. She worked tirelessly

at the gym and poured over the mountain of material an astronaut must grasp before

setting foot in a Space Shuttle. Though the average person would find the amount

of minutiae and the sheer volume of information staggering, it was all in a day's

work for Dunbar. "You have to keep up – that's the bottom line," she says matter

of factly. After all, the astronauts were preparing for the weightless world in

which pennies float, liquids form spheres, and life turns upside down.

A Space Hero is Born

Dunbar and crew on her first space flight in 1985. She may have been the lone female on the mission, but Dunbar never gave the gender barrier much thought.

STS-61A NASA photo.

Dunbar and crew on her first space flight in 1985. She may have been the lone female on the mission, but Dunbar never gave the gender barrier much thought.

STS-61A NASA photo.

In 1985, NASA called Dunbar to astronaut duty. It was the chance of a lifetime and a dream fulfilled. Dunbar was set to become the seventh American woman ever to fly in space. It was a Spacelab mission. A shared venture between the U.S. and Europe, Spacelab was a reusable laboratory that orbited Earth in the Payload Bay of the Space Shuttle. West Germany bought and paid for the mission.

"The Germans were very interested in the science and the microgravity environment,"

explains Dunbar. "They wanted to become involved in human spaceflight and using

that flight to inspire their youth in a post-World War II environment."

As mission specialist, Dunbar's key role was to carry out the work of Principal

Investigators from several countries using the microgravity environment of outer

space. The experiments would benefit human physiology and space exploration. To

prepare, Dunbar flew to Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Italy to meet with

the researchers. The personal connection was vital. She and her crewmates would

serve as the investigators' "eyes and ears" in orbit.

Allowed to take small personal possessions on the approaching flight, Dr. Dunbar

carefully chose pieces of her mother's jewelry and a belt buckle that belonged to

her father. October 30, 1985, Challenger (STS 61-A) tore through the skies with

Dunbar and her team on board.