A Fruit Fly Named Smart Willie

Frequent travelers of the shuttle, fruit flies share much in common with human-size astronauts and contribute to a multitude of experiments revealing the impact of microgravity on the human body.

University of Wisconsin-Madison

photo.

Frequent travelers of the shuttle, fruit flies share much in common with human-size astronauts and contribute to a multitude of experiments revealing the impact of microgravity on the human body.

University of Wisconsin-Madison

photo.

While Dunbar sat strapped to a seat in the orbiter, a crewmate a fraction of her

size discovered newfound freedom. Affectionately called "Smart Willie" by a crew

member, the fugitive fruit fly broke out of a research cage and to the best of anyone's

guess, his ultimate demise. First spotted by crew and watched on German television

in ground control, "Smart Willie" floated and tumbled about in the weightlessness

of space. Unable to fly, "Willie" grabbed onto any surface he could find, clinging

for dear life.

A miniscule speck with wings, Willie's similarities to human beings appeared downright

implausible. But there were many: the genes, cellular makeup, brain cell development,

and behavior. As it turned out, fruit flies – shuttle regulars - promised to help

extend missions by revealing the impact of space on the human body.

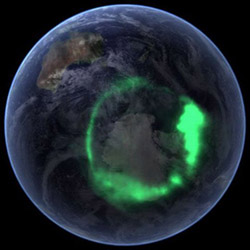

The Southern Lights, one of Dunbar's most vivid memories of space flight, are a stunning sight. Solar wind carries electrical particles from the Sun to Earth's magnetic field creating unforgettable color at Earth's South Pole.

NASA photo.

The Southern Lights, one of Dunbar's most vivid memories of space flight, are a stunning sight. Solar wind carries electrical particles from the Sun to Earth's magnetic field creating unforgettable color at Earth's South Pole.

NASA photo.

Willie spent his final moments contributing to the cause on board Shuttle Challenger

with a host of fellow fruit flies and eight human crew mates, including Dunbar on

her maiden voyage to space.

Nearly 30 years had passed since an 8-year-old scoured the skies over Outlook for

a small Russian satellite. Now she was seeing our majestic world from orbit with

her our own eyes.

At an inclination of 57 degrees to the Equator, Dunbar could see the South Pole

to her right and the North Pole to her left. She saw the Southern Lights – formed

by a combination of the Sun's particles and Earth's magnetic pole producing brilliant

color and light.

"You float there in front of the overhead windows that are now pointed at the direction

you're flying. And I could only think about being on the deck of the Starship Enterprise.

(laughing) You know, going where no man or woman has gone before."

The Washington native had done it. With a team of astronauts, she carried out roughly

100 experiments during that first mission and the flight was hailed a success.

Catch of the Day

In 1990, Dunbar returned to space (STS-32) chasing an orbiting satellite that had

been circling Earth six years. By the time Columbia, first orbiter of the shuttle

fleet, closed in on the satellite, the moving target had looped Earth nearly 33,000

times. The delicate dance involved a 178,000-pound (80,739 kg) orbiter and a 21,400-pound

(9,707 kg) satellite known as the Long Duration Exposure Facility or LDEF. The satellite,

taxied to space in 1984 by a shuttle, was soaking up all it could from the environment.

LDEF, held a treasure of knowledge about our outside world. But it had been orbiting

too long due to delays from the Challenger tragedy that temporarily grounded the

Space Shuttle Program. The satellite was slowly falling out of orbit. Waiting in

the wings for the dramatic rescue were some 200 principal investigators in nine

countries across the world. They wanted LDEF's data.

At the White House, Dunbar shakes hands

with President George H.W. Bush and First Lady Barbara Bush after successfully nabbing

the orbiting satellite, LDEF, in 1990.

At the White House, Dunbar shakes hands

with President George H.W. Bush and First Lady Barbara Bush after successfully nabbing

the orbiting satellite, LDEF, in 1990.

On a mission to snare the de-orbiting satellite, Dr. Dunbar and team began to rendezvous

with LDEF. Already hard to fathom for the layman, the stunt becomes impossibly tricky

when you consider the cramped quarters of Columbia's Cargo Bay. It was only 15 feet

(4.6 m) wide. LDEF stretched 14 feet (4.3 m). The Columbia team had all of 12 inches

(30.5 cm) to spare.

In a mind boggling maneuver, Dr. Dunbar nabbed the satellite with a 50-foot (15.24

m) robotic arm designed by the Canadian Space Agency. Slowly she began inching the bus-size satellite into the bay.

"I would not have been able to capture

it if (Mission Commander) Dan Brandenstein had not been able to maneuver the shuttle

close enough, in exactly the right spot so the arm could reach it," Dunbar says.

"That was key, because you have two bodies now orbiting the Earth at 17,500 miles

per hour (28,164 km/h). … You're always excited before and after, but in the middle

of performing, whether you're an athlete or a race car driver or a pilot, you are

really focusing on what you're doing. Everything you've done, in terms of training,

it's like your finals. If you've been in the middle of a final, are you thinking

about your emotions at that time? You think about answering the question on the

test."

To those holding their breath back on Earth, Dunbar passed the test with flying

colors. LDEF appeared battered and bruised as expected - but remarkably intact after

six long years in the wilds of outer space.

Training with the Cosmonauts

Dunbar roughs it with cosmonauts while immersed in survival training near Star City to backup Dr. Norman Thagard, first American to ride the Russian’s Soyuz to space. Photo from Col. Terrence Wilcutt.

Dunbar roughs it with cosmonauts while immersed in survival training near Star City to backup Dr. Norman Thagard, first American to ride the Russian’s Soyuz to space. Photo from Col. Terrence Wilcutt.

It wasn't long before Dunbar ventured to the wilds of Star City, 20 miles (32 km)

or so from Moscow. The once top-secret Gagarian Cosmonaut Training Center invited

the best, brightest and bravest across the world to train for space travel. The

center was named for Yuri Gagarin, who rose to international stardom in 1961 when

he became the first human to orbit Earth. (Russia's first "cosmonaut" was a dog.

Sputnik II launched a canine named Laika into space in 1957.)

Astronauts Norman Thagard and Bonnie

Dunbar at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center. NASA photo.

Astronauts Norman Thagard and Bonnie

Dunbar at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center. NASA photo.

In 1994, Dr. Norman Thagard was ready to make history himself as the first American

to ride the Russian Rocket Soyuz to space. But Thagard needed a back-up and few

volunteered, according to Colonel Terrence Wilcutt, a NASA colleague. The Soviet

Union had collapsed, the U.S. presence there was minimal, and the winters were bitterly

cold.

But with three missions behind her, Bonnie Dunbar embraced the challenge. In nothing

flat, she had her bags packed for Star City. Dunbar made great Russian friends during

her 13-month stay and trained with cosmonauts Anatoly Solovyev and Nikolai Budarinan

to bring two countries, once at odds, closer together. The crew trained on a multitude

of experiments provided by both the U.S. and Russia.

On March 14, 1995, Dunbar witnessed history in the making. Thagard boarded the Russian

spacecraft Soyuz for a nearly four-month visit to Mir, the 135-ton Russian Space

Station that orbited Earth for 15 years. (In 2001, Mir was intentionally de-orbited

and broke apart over the Pacific Ocean.)

From Pointing Weapons to Peace

By this time, the protracted Cold War standoff between the United States and Russia

had thawed dramatically. Two nations stood on the brink of uniting in orbit to signal

a new beginning. Soon, they'd create a massive complex in space to pave the way

for the International Space Station. The Atlantis-Mir coupling would stretch 234

feet (71.3 m), the length of a Boeing 747.

A breathtaking view of Earth shows the

nose of Space Shuttle Atlantis. The photo is taken from Russia's MIR Space Station during the docking. STS-71. NASA photo.

A breathtaking view of Earth shows the

nose of Space Shuttle Atlantis. The photo is taken from Russia's MIR Space Station during the docking. STS-71. NASA photo.

It was June 27, 1995. Dr. Bonnie Dunbar was about to make her fourth trip into space

aboard Shuttle Atlantis (STS-71). It whisked away from Earth with five Americans,

two Russians, and a host of medical experiments on board. The flight marked the

100th mission for the U.S. space program and the first international docking in

two decades. Atlantis delivered cosmonauts Solovyev and Budarin to Mir and picked

up Dr. Thagard. To gauge the impact of space on the human body, the Atlantis team

conducted medical evaluations on Dr. Thagard and the two cosmonauts.

A New Era in Space

The historic Mir docking in the summer of 1995. Space Shuttle Atlantis latches onto the Russian Space Station Mir symbolic of a new era for two nations once locked in the Cold War. STS-71. NASA photo.

The historic Mir docking in the summer of 1995. Space Shuttle Atlantis latches onto the Russian Space Station Mir symbolic of a new era for two nations once locked in the Cold War. STS-71. NASA photo.

The United States and Russia were poised for the docking. "You can't make this unbelievable

transition from pointing weapons at one another to working together without bumps

in the road," NASA chief Daniel S. Goldin told The New York Times of the dark history

that had once plagued the two nations. "But the relationship is rock solid. This

proves that if you put your mind to something and search for common interests, you

can build bridges."

High above Central Asia and at breakneck speeds–the main engines of Atlantis fired

for 45 seconds. The orbiter positioned itself within nine miles of its target. "We

can see Mir's running lights," Captain Gibson told Houston. One more firing and

the two massive spacecraft almost connected.

"You never think about making history while you're there," says Dunbar. "If you're

doing that you're not putting all your brain cells where they need to be."

A support team spread across the world gave the OK for the link-up. "Houston," Captain

Robert Gibson radioed to ground controllers, "we have capture." Applause erupted.

Dunbar is still impressed the docking occurred on the first attempt.

U.S. astronauts and Russian cosmonauts happily greeted each other in space. They

were hundreds of miles from the surface of the Earth with no hint of the Cold War.

Dr. Dunbar affixed an Atlantis-Mir crew patch on one of the station's switch boxes

marking the event.