The Puget Sound Navy Museum, housed in

historic Building 50, is located near the ferry terminal in downtown Bremerton.

The Puget Sound Navy Museum, housed in

historic Building 50, is located near the ferry terminal in downtown Bremerton.

Many thanks to: Judge Robin Hunt, Dianne Robinson and the Black Historical Society of Kitsap County, Alyce Eagans, Hazel and Althea Colvin, Dr. James T. Walker Jr., Carolyn Neal and the Kitsap Regional Library, Linda Joyce, Jim Campbell and The Kitsap Sun, Professor Quintard Taylor, Justice Charles Z. Smith, Don Brazier, Andy Oakley and the Bremerton Police Department, Bonnie Chrey and the Kitsap County Historical Society Museum, Danelle Feddes, Heather Mygatt and the Puget Sound Navy Museum, Cristy Gallardo and the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard.

The Puget Sound Navy Museum, housed in

historic Building 50, is located near the ferry terminal in downtown Bremerton.

The Puget Sound Navy Museum, housed in

historic Building 50, is located near the ferry terminal in downtown Bremerton.

The Puget Sound Navy Museum, located in an historic building near the entrance to the ferry terminal in downtown Bremerton, now features an exhibit on African Americans who have worked at the naval shipyard. "Faces of the Shipyards," which runs through spring 2010, includes photos, artifacts and memorabilia. James and Lillian Walker, Dick and Faye Turpin, Marie Greer and Loxie Eagans, well-known Bremerton residents, are among those spotlighted. Admission to the museum is free. Hours are 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Saturday and 1 to 4 p.m. Sundays. The museum is closed Tuesdays from October to April.

Sinclair Heights boy makes good: A well-illustrated, comprehensive history of the shipyard - NIPSIC to Nimitz, Louise M. Reh and Helen Lou Ross (ISBN 0-931475-02-3); Naval Memorial Museum of the Pacific, Bremerton, 1991. - takes note of a Sinclair Heights boy destined for greatness in the music world: "Quincy Jones Sr., a carpenter from Chicago, and his two sons arrived at Sinclair Heights on July 4, 1943. Their house was small and poorly heated, but for the boys it was a wonderful place; it was in a wooded area with much to explore and wild berries to eat. The older boy had been interested in music while in Chicago; now he received encouragement from musicians in the Navy Yard and from teachers in Bremerton Schools," including Joseph Powe, who had a dance band on the side. A barber named Eddie Lewis also gave him some pointers, Jones recalls.

Danelle Feddes, assistant curator of

the Puget Sound Navy Museum, in the exhibit hall, featuring "Faces of the Shipyards"

through spring 2010.

Danelle Feddes, assistant curator of

the Puget Sound Navy Museum, in the exhibit hall, featuring "Faces of the Shipyards"

through spring 2010.

In The Complete Quincy Jones, a wonderfully packaged autobiography (Insight Editions, San Rafael, CA, 2008, ISBN: 13:978-1-933784-67-0), Jones documents the discrimination his father faced in trying to keep a job in the industrial wing of the national defense program in Chicago, despite the fact that he was an expert carpenter. One day, when he picked up his sons after work, he abruptly announced, "We're leaving." Quincy Jr., who was 10, sputtered, "Can we get our toys?" Daddy said no. "We don't have time." They hopped a Trailways bus and headed for Bremerton. "They had a place way out of town called Sinclair Heights," Jones says. "We had to walk up a hill forever, three miles. That's where they put all the black people."

Paul de Barros, an author and music critic, features Jones in his book on the roots of jazz in Seattle, Jackson Street After Hours (ISBN 0-912365-86-2, Sasquatch Books, Seattle, 1993). In it, Jones recalls that the government and the white power structure in Bremerton made sure that Sinclair Heights "was way away from town. … They also didn't put phones in the homes. You had to go to a telephone booth. They didn't want the black people to get so comfortable there after the war. They wanted them to get out."

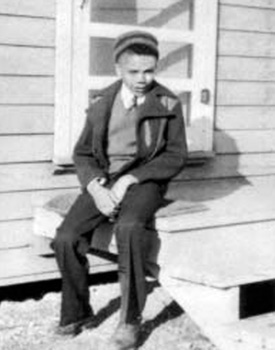

Quincy Jones Jr. as a boy.

Quincy Jones Jr. as a boy.

In a vignette entitled "Delin-Quincy" in his own book, Quincy recalls, "When I got to Bremerton, an armory was our recreation center. We heard there was a new shipment of ice cream coming in with some lemon meringue pie. We thought that this was a great chance for us to use all of our training with the greatest gangsters in the world as kids. So we broke in there, ate up the pie, and roamed around …" He ended up in the supervisor's office, and had a life-changing encounter with "a little spinet piano over in the corner." He "touched it, and every cell in my body and every drop of blood said, 'This is what you're gonna do the rest of your life.' So I stayed and practiced the piano all day after that." The rest, as they say, is history.

When they moved to Seattle in 1947, Jones attended Garfield, Seattle's most diverse high school. On trumpet, he was a star performer with the school band and hailed as a prodigy by the local dailies. With his own band and other combos, he often had three gigs a night, and his arrangements were played by the likes of Count Basie. He also met an amazingly eclectic teenage musician from Florida who had been blind since childhood, Ray Charles Robinson. Ray was playing at the Black Elks Club on the north side of Seattle's Jackson Street.

"Q" and Ray Charles became legends in their own time. Jones has won 27 Grammys, including one for producing "Thriller," Michael Jackson's landmark pop fusion album. He is also an internationally honored humanitarian who produced "We are the world."

Lillian Walker remembers encountering Quincy Sr. when she managed the Sinclair Heights Post Office, but neither of his livewire sons made a big impression. "Years later when I read about Quincy, I'd say, 'I knew that kid!' But I really didn't know him. … He sure is a brilliant man!"

Quincy Jones graduation picture from

Garfield High School in Seattle in 1948.

Quincy Jones graduation picture from

Garfield High School in Seattle in 1948.

De Barros' book, which features a marvelous photo gallery by Eduardo Calderon, also notes the racial culture tension in Seattle as a throng of southern Negroes arrived to work in the war industry: "For a while, there was friction between the older black community and the new arrivals." The newcomers wore dungarees on the street, tied their heads in handkerchiefs, ate watermelon on the curb and were "noisy." And "though no one dared speak publicly of it, there was also an issue of skin tone within the black community. The new immigrants, largely from the Southwest and the South, were not only more rural, less educated and 'ill-mannered,' they were also darker-skinned."

Lincoln's musings: This from Ronald C. White Jr.'s wonderful new biography, "A. Lincoln": Heartsick as the Know-Nothings made inroads into the Whig Party, Lincoln wrote to his old friend Joshua Speed in 1854: "Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that 'all men are created equal.' We now practically read it, 'all men are created equal, except negroes.' When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read 'all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and catholics.' When it comes to this, I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty, Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, without the base alloy of hypocrisy."

The "Negro Problem": Bringing it all back home, as Bob Dylan once said, is Nard Jones' widely read 1947 book Evergreen Land, A Portrait of the State of Washington." Jones, then one of the Northwest's leading writers, discussed black migration here in the 1940s and offered a singularly unprophetic comment about Mexicans. He noted that in World War II, "With the Army and the Navy and the Coast Guard naturally came the workers. Towns that had rarely glimpsed a Negro accustomed themselves (or did not) to Negroes by the hundreds. Some of the Negroes were from the deep South and not too happy in the far Northwest, but they were happier than the Mexicans who were brought in by rail and truck to act as farm labor. To a Mexican the Pacific Northwest is a dismal place indeed, where the sun shines briefly or not at all. They did not sing very much, those Mexicans. They did not have the heart to fight or love. They have departed from the Evergreen Land now and are glad of it. But the Negroes, most of them, have wanted to stay."

Earlier, Jones mentioned the genesis of "the Negro problem" in Washington, noting that Captain William Clark of the famed Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-06) brought along a Negro, "a six-footer called York." "The fact that he was the slave of Captain Clark, and black, does not seem to have depressed him. He liked to jig for the awed savages by the camp fire and he delighted in performing feats of strength for them. Our western romanticists to the contrary, he was probably of more value to the safety of the party, therefore, than Sacajawea. Until World War II, Oregon and Washington were unfamiliar with the Negro problem. Now that they know what a Negro is, it is of historic interest to note that York, a bona fide member of the party of Lewis and Clark, was undoubtedly the first colored emigrant to the Pacific Northwest."

Lewis and Clark scholar David Nicandri, the director of the Washington State Historical Society, sets the record straight in several instances: He is aware of no known basis for asserting York's stature. As for the notion that York was not depressed to be a slave, "not during the time of the expedition perhaps, but our impression for that fact would have been Clark's own journal; hardly an objective source on the matter. It is known, after the expedition, that York took considerable objection to his status and Clark's unwillingness to free him." Moreover, "rarely was the party's 'safety' in jeopardy, and probably the one time it was, on the Bad River confluence with the Missouri, the flatboat's swivel gun" was the key factor. As for Sacajawea's value, "here Jones seems to be anticipating an argument that became popular much later, that she was some sort of an ambassador for the party." Jones' assertion that until World War II, Oregon and Washington were unfamiliar with "the Negro problem" is "an exaggeration to be sure," Nicandri adds. "There were slaves here, illicitly, in the 1850's. Settlers out this way were quite aware of the slavery issue." Characterizing York as the first colored emigrant to the Pacific Northwest, "depends on your definition of 'colored,'" the respected historian says. "If we mean 'people of color' in contemporary usage, definitely not. I like to tell people that if we saw the first non-Indian settlers of Washington (at Neah Bay, 1790) we would recognize them today as being of Mexican ancestry."

Chief Gunner's Mate Dick Turpin in the

1920s. Puget Sound Navy Museum

Chief Gunner's Mate Dick Turpin in the

1920s. Puget Sound Navy Museum

A medal long overdue? Dianne Robinson, founder and curator of the Black Historical Society of Kitsap County, has documented the arrival of blacks and Filipinos at the Puget Sound Navy Yard. Her research indicates there were more than 200 blacks in the Sinclair Inlet area by 1912 and most of the men worked at the Navy Yard. One was the legendary John Henry "Dick" Turpin (1876-1962), a U.S. Navy chief gunner's mate who retired in Bremerton in the 1920s and went to work as a master rigger driver at the Navy Yard. He was also a master diver. His wife Fay was a rivet passer during World War I. "Tall, erect and courtly," Turpin had been one of the Navy's first African American chief petty officers. He was highly respected in the Bremerton area, providing lodging to newly arriving blacks, including James and Lillian Walker. Handsome as a movie star, even in his 70s he could do handstands. Robinson and other black historians believe Turpin should have received the Medal of Honor, for which he was reportedly nominated not once but twice during his Navy service. A strong swimmer, he survived the sensational explosion that decimated the battleship U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor in 1898, and is credited with heroic life-saving efforts in the wake of the blast. In 1905, Turpin was aboard the U.S.S. Bennington in San Diego Harbor when its boiler exploded, and saved the lives of shipmates. He is also credited with helping invent the underwater cutting torch. During World War II, Turpin made "inspirational visits" to Naval Training Centers and defense plants, and was a guest of honor on the reviewing stand in Seattle when the first black volunteers were sworn into the Navy shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor. More on Dick Turpin

Meantime, Some 200 Native Americans worked in the Navy Yard during World War II, including Daniel Working Bull, the grandson of Sitting Bull.

Art Morken in 1961. Bremerton Police

Department

Art Morken in 1961. Bremerton Police

Department

A revered cop: Arthur Norman "Art" Morken (1909-1986), the Bremerton police chief fondly remembered by civil rights activists, joined the force in 1934 and quickly rose through the ranks to captain in 1941. He was acting chief during the tumultuous war years and became chief in 1961 with the retirement of Charles "Slats" Lewis. Aft er retiring the following year, Morken was elected Kitsap County sheriff and served until retiring again in 1979. As a youth, Morken was a lifeguard at Lions Beach on Kitsap Lake and "saved many lives." Part of Morken's legacy, according to the Police Department's Web site, "was his love of children. He is remembered for starting the Safety Patrol Program and taught kids life-long values that he shared and instructed in the program. He instilled values such as respect for elders, respect for law enforcement and to be punctual. He taught kids who were members of the Safety Patrol Program that they were providing a service to the community and providing service to the community was important. All the kids knew and respected him and he always had time for them." The city's new police headquarters was named in Morken's honor in 2007.

Excellent article: Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Fall 2007, Boeing Aircraft Company's Manpower Campaign during World War II, by Polly Reed Myers. A painstakingly documented overview of racism in the war industry on Puget Sound.

Key reference works: Washington, A Centennial History, by Robert E. Ficken and Charles P. LeWarne (ISBN 0-295-96693-9); University of Washington Press, 1988. A factual, highly readable history by two of the Northwest's most respected and prolific historians. Also, The War Years, A Chronicle of Washington State in World War II, by James R. Warren (ISBN 0-295-98076-1); University of Washington Press, 2000. This is a fascinating year-by-year overview of Home Front Washington.

Compelling interview: Charleen Burnette, public access manager and moderator for Bremerton Kitsap Access Television's "Around Kitsap" program, aired a lively interview with Lillian Walker and Linda Joyce on Aug. 29, 2008, as the Kitsap County YWCA celebrated its 60th anniversary. The videographer for BKAT was Michael R. Downum. Bremerton Kitsap Access Television

Student project: Cecelia R. Walker, a student at Olympic College, interviewed Mrs. Walker in 2009 and wrote a warm profile for her class on "Women in American Culture." We thank her for sharing it.

BlackPast.org, a 3,000-page reference center on African American history; Website director is Quintard Taylor, the Scott and Dorothy Bullitt Professor of American History at the University of Washington, Seattle. Sinclair Park

The Black Historical Society of Kitsap County

HistoryLink.org: History of the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard